Sometime in the year or two before Daddy died, he and Momma and I went to see a movie together, The Lion in Winter. It has remained one of my top ten ever since because of the incredible writing, the acting, and because it introduced me to Anthony Hopkins, who played Richard the Lionheart, the second son of Henry (Peter O’Toole) and Eleanor (Katherine Hepburn). Richard was Eleanor of Aquitaine’s favorite, in a not good way. The dialogue was the sharpest, most clever interchange I had ever heard. As I sat watching those people on the screen hurt each other so bitingly with words, I almost felt embarrassed to be with my parents. It’s as if the actors were displaying the rage that was in my heart, and the witty but harsh way I wished I could communicate it. I almost felt that my folks must know, and that my secret inner anger and grumblings were being exposed.

I never dared the drama thing myself, but I secretly wanted to. Mr. LaCerte was very inventive, and had such a great group of actors while I was in high school. They built a Circle Theater seating about 50 people, and put on a whole series of small plays and evenings of one-acts. They did Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, and it was awesome to witness friends of mine in such dramatic and moving parts, acting practically in our laps. The intimacy and immediacy were stunning. They did The Fantasticks and it was absolutely magical to see people I knew transformed into romantic figures.

That happened again when the whole school put on West Side Story on the big stage. My friend and carpool buddy, Jackie Stalcup, played Maria and did a wonderful job. I was pulled into the story and forgot she was Jackie. And John Locke, a “bad boy” who loved music enough to tolerate being in Madrigals, played Tony as a passionate lover. The whole performance was fantastic, and I went as many times as they performed it. Of course I listened to the album endlessly and memorized every song. I can see myself standing in my yellow bedroom, looking out the window and singing “I Have a Love” at the top of my lungs, and my mom hollering up the stairs, “Honey, isn’t that song too high for you?” “No!” I hollered back, “Besides, I’m working on it!”

Chris Stivers and a friend of his named Rick Cordova arranged the Bernstein score for two pianos and their performance alone was a stunning feat. Rick later went on to conduct opera. Chris had another friend, Michael Jacobs, who was Jewish, funny, musical and wore Aramis cologne. One day in our senior year, Mike asked me what my dad did. I made a quick decision not to make Mike uncomfortable by telling him my dad had just died that summer, and I responded, “Not much,” cracking myself up. Mike Jacobs became my big high school crush, and one day he played privately, just for me, a delightful, sprightly little melody he had composed. Later on, it crushed me when he told a group gathered for a cast party that he dedicated that perky little ditty to another girl. Chris later told me Michael was gay, and that was another heartbreaker.

Chris and I also had heart to heart talks about his discomfort with his girlfriend and his relative comfort with his guy friends. Once again I felt compelled to try to persuade him that it made perfect sense, because he had such a history with his guy friends and barely knew the girl, that he understandably felt more comfortable, even more affectionate, being with these guys. I didn’t want anybody to feel they were fated with being a homosexual and had no choice in the matter, although that’s what most people believed.

I learned a lesson in high school about the quickly passing nature of physical beauty. In one of my classes I sat behind a guy with the most gorgeous hair. It was dark brown, almost black. It was shiny. It was slightly wavy, thick, and long. I fantasized playing with it, stroking it. I was in love with his hair. His name was Perry Laness, and we never had a single conversation, but if we had, the first thing I would have asked him for was permission to touch that hair. Well. One day he comes to class and it’s…gone. No, he didn’t shave his head, but that glossy, thick, long beautiful stuff was cut to a normal length and he looked…average. My love affair with Mr. Laness had ended without a word. In my heart I heard, “You had better love more than the exterior of a person, because it will change.”

The Christmas of my senior year, Mr. LaCerte and Mr. Fontana joined forces to produce Gian Carlo Menotti’s operetta, Amahl and the Night Visitors. It had been written for Charleston’s Spoleto Festival and it had been presented on TV, but I had not been exposed to it before, so to me it was a revelation. It was my first time to hear an opera in English, and the melodies were so beautiful and moving that I ended up learning the whole operetta note for note, with everybody’s part. I learned the overture on the piano, and wore my mother out with the constant repetitions, I’m sure.

I longed to be one of the shepherds in the chorus, but the decision was made to have the Madrigals play those parts and hold no tryouts, and once again I felt unfairly excluded. It hurt, because I loved the music so much and thought this was finally a way to get back onstage without the spotlight being on me. Since I had been rejected for Madrigals, I was automatically rejected for this role - a double injustice! And Dieva Perez told me she didn’t even really want to be in Madrigals! Why did people who didn’t care seem to get into groups like this, when people who really wanted to were left out? What a world.

Singing in the Morningside choir brought more “close encounters” with Hollywood. While I was in high school, our choir was among those chosen for some special events. We participated in the Living Christmas Tree at Disneyland, and as we processed down Main Street and into the “tree” formation, I passed by Jimmy Stewart, just a few feet away. He was narrating the Christmas story that year.

Speaking of the contacts appointments triggered another memory for me. One morning I woke up and thought it was very strange that my closet door was open and the light was on in it. I went into my parents’ bedroom – they were still in bed – and asked if one of them had come in my room during the night. No – that was strange. Then I headed down the hall to my bathroom, and noticed something odd about the guestroom across the hall. A couple of small pieces of luggage were lying on the bed – they had been in my closet. Things were getting stranger.

I headed downstairs and found the sliding glass door to the den wide open and the curtains blowing. The couch cushions weren’t right, and under them I found my mom’s billfold. Apparently, someone had come in the house while we were all asleep, looking for money. Whoever they were, they had been in my parents’ room as well, because that’s where my mom’s purse was with her billfold inside.

Thank God none of us had woken up! How scary that would have been. Nothing else in the house seemed disturbed, but I felt a shock take hold of me. Later on I learned a name for the feeling – violated. Someone had been in my bedroom with me lying there asleep. They could have hurt me, or killed me. At the very least, they were trying to steal. Ever since I had read that TIME magazine article as a ten year old in Germany, I had been afraid of someone breaking in my house. Now that it had actually happened, I didn’t feel afraid anymore. I had lived through it. But I hated the feeling I did have, a feeling of helplessness.

That afternoon I had a contacts appointments downtown, so Daddy picked me up at school and took me. As we were about to pull into the driveway off Crenshaw, earlier in the afternoon than we would normally have arrived home, we were shocked to see a couple of policemen in our yard with rifles aimed at the upstairs windows. There were several police cars in the circular driveway around the old dead tree. The police had determined that the intruder had first gone to the Davis house, on the northeast corner of our property, stolen a gun out of the nightstand by their bed without waking them, then tried to get into the Kinneys’ house next to us but didn’t, and then came into ours. So now we knew they were armed when they were in our house, with us asleep.

In my closet ceiling there was a small opening to the attic, with a square piece of wood that set down in it. That wood was a bit ajar, and I didn’t know if the police had done that in searching the house, or if the intruder might actually have managed to go up into the attic. For a few days after all this, I was scared that the thief was hiding in the attic and would appear at any time. Though the police assured us that they had thoroughly searched the house, I still felt pretty creepy about the whole incident.

For my fifteenth birthday, Daddy took me out to dinner downtown and to Pickwick Bookstore. He had never done either of these things before. For my birthday gift he let me buy a certain number of books there, whatever titles I wanted. I remember sitting alone in the car while he went to check on whether a restaurant was open. I thought to myself, “Why are we alone? Why don’t I feel okay about it? What’s wrong with him, or what’s wrong with me? This is confusing.” One of the books I bought that night was The Prophet by Khalil Gibran. It appealed to my sense of mystery and poetry, and my interest in philosophy. Another of the books I chose that night was Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver. This volume proved to be a problem.

Daddy and I were gardening together one Saturday. We were pulling weeds out by the huge dead tree in the center of the circular driveway, where we had planted multi-colored sweet peas. (We didn’t have that huge dead tree removed because it was so picturesque.) Daddy informed me that he was considering sending me to Searcy, Arkansas to go to Harding Academy for my senior year in high school. He felt I needed some “straightening out.” He told me that they wouldn’t allow such books as Soul on Ice at Harding. They would teach me how to act like a lady.

From Soul on Ice we slid into a brief discussion of racism, and he declared that his grandfather had owned slaves and had been good to them. “Daddy, can you not see that it’s impossible to say you own a human being and at the same time say that you are good to them?” I practically shouted. We were definitely at an impasse. And he was thinking about sending me to what sounded like reform school!

That spring or summer, I was home sick in bed one day. I had a high fever, and I was foolishly reading Edward Albee’s play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? This was a dangerous combination. Every time I would get tired and try to sleep, my brain would keep making up fresh dialogue for the characters. Needless to say, the strife in George and Martha’s marriage resonated with me because of my struggles with Momma. I had loved and hated Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie for the same reason. I had such an urge to strangle that Southern belle, because she went on and on with her hurtful, prideful, flamboyant comments while her daughter wilted in humiliation.

Anyhow, Daddy came home early from work that day because he had just attended a funeral. Jackie Pepperdine was a niece of the founder of the college, and she had been a student with us in Heidelberg, so we had known her for some years. The Sunday before, she had been driving to church when her car ran into a pole on the freeway and she was instantly killed. Daddy had never experienced a death before where people rejoiced because they knew the person was with the Lord. All he had ever seen was Nannie’s (his mother’s) country style, wailing and moaning and keening over a grave, in that scary old Southern way. The joy in the memorial service for Jackie had stunned him. But instead of offending him, it had made him want to understand.

He talked with me about it. I explained to him that Jackie’s friends knew she loved the Lord and wanted to spend eternity with Him, and that she was secure in her salvation. Some of them were probably jealous that she made it home first! It wasn’t irreverence or insanity that made them happy about her death, but a deep knowing that the love of Jesus would keep her wherever she was, and that they would be reunited with her in the final resurrection someday. So they had lots of reasons to rejoice. He had never heard the like of this before. I sensed that he felt grateful for the insights and encouragement, and he didn’t argue. I couldn’t have imagined that I was literally giving him a pep talk for his own soon passing.

That summer was our last family vacation together, but of course we didn’t know it at the time. We drove north to Paso Robles and spent the night at the same place we stayed every year. It was a Spanish hacienda-style series of buildings, with an open courtyard in the middle. Daddy asked me to come down and sit with him in the courtyard, and we talked. Well, we tried to talk. First I would say something. It would be a long paragraph of ideas, emotions, thoughts, an attempt at getting him to hear my heart. Then there would be silence. Then he would say something brief. Then another long paragraph from me. And then the silence. This continued for awhile, and then he sighed deeply and said, “Either you’re much smarter than I am, or you’re crazy.” My heart sank. I hated both options he was offering. They both made me feel alone. I felt my attempt at winning his approval, or at least his comprehension, had been a failure.

If you had a high school kid that wrote an essay like the following (Daddy never read this one, but it was typical of my thinking at the time), perhaps you would find conversing with her more than a little daunting as well.

“Perhaps one of the things that makes the Southern churches’ injunctions against dancing, drinking and so many other potentially but not innately evil things so maddening, is the apparent hypocrisy involved. Paul warns us not to ‘be conformed to this world’ but rather to be renewed within – to walk proudly to the beat of the other Drummer. And the church here does this – in some areas and to a certain extent – proudly. But the children must wonder, ‘Why should I make myself seem strange or different in these ways when my parents and I are so much like our friends in every other way?’ Certainly it is a good thing to keep one’s body pure for the Lord – but what about over-eating (self-condemnation here), pill-popping, sex without love? And most certainly we should not forget the inward man. We claim to be Christ-ones, and yet we so often disregard the fact that, since Christ, the sins of our inner selves are judged and condemned with almost greater severity than before – for ‘when the light had not yet come, the darkness was without condemnation; but when the light came, it showed the darkness to be what it was, and the darkness stood condemned.’

“We are unlike the world: we do not dance, we do not drink, we do not smoke.

“We are friends of the world: we love money, we hate a man because of his color, we are barbaric in the way we live and in the way we die.

“I wonder. Which would be better: a man who smokes and loves, or one who doesn’t smoke and hates?”

Yes, I had a serious problem with my Southern heritage. God has such a great sense of humor. I would never in a million years have guessed at that age where I would be living for the past thirty years. I would have been horrified!

Norvel had his fiftieth birthday while we lived at the Gray House, and one night on the patio we threw a big birthday party for him. It was the only truly large event we ever hosted, and I was up on the balcony off my parents’ bedroom surveying the crowd. Norvel, I was shocked to find out, hated getting older. In fact, his autobiography was later entitled Forever Young. He really despised having a fiftieth birthday, and all the faculty and staff at the party were sort of roasting him and harassing him about it. He hated the intimations of mortality that this represented, and could never have imagined that only a handful of years later his host would be gone. Daddy died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-four.

It was the summer of 1969. Daddy had been depressed for a couple of years because the administration had promoted him from Comptroller (where he was responsible for anything and everything financial, including plant management, student loans, work/study arrangements, purchasing, faculty salaries, all the money stuff) to Vice President in charge of Planning. He didn’t want a promotion. He really liked overseeing the whole operation financially, even though he was pretty severely stressed by it.

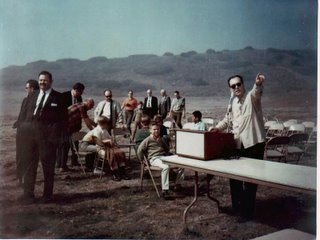

Now he was sent to fundraising school, which he despised, and given the job of helping to locate the next Pepperdine campus. We really needed to leave South Central Los Angeles. Mothers were not comfortable sending their children to Pepperdine because of its location. Many sites were proposed and many offers considered, but finally they settled on the property at Malibu. My dad presided along with Norvel at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Malibu campus, when it was still nothing but dirt and dreams. He's at the podium here, pointing to where some building will be constructed.

Much has been written on the history of the Malibu property, so I don’t need to repeat that here. Suffice it to say that the Rindge family had owned the twenty miles of coastline down to Santa Monica, and there was no traffic except on their little private railroad. They owned the Malibu Pottery, which made tiles based on designs they collected from around the world. There was a larger home up in the hills near the Serra Retreat that had been lost in a fire, but a second house, the smaller mansion down on the beach next to the Malibu Colony, was still intact.

It had been empty for some years. The house had been donated to the State of California, but the State couldn’t afford the upkeep at that time, so it was neglected and in some disrepair. Norvel worked a deal with the State officials. The Youngs would live in the house, and pay a certain amount – I think it was $30,000 – each year toward its upkeep and restoration, until the State could afford to take it over again. He was counting on several good years, and it did turn out that way. So later on, in 1972, before anything was built on the land that had been donated, the Youngs left the house on the L.A. campus behind and moved to the beach house.

But back in 1969, there came an offer that Daddy couldn’t refuse. A smaller Church of Christ school in Portland Oregon, Columbia Christian College, was in financial distress, something like the red-ink crisis Pepperdine had suffered a decade earlier. Would J.C. come up and rescue them, and serve as their President? This was the kind of challenge he loved, and he could move out from under Norvel’s shadow and the disappointments of their working relationship. (He never said this overtly, it was something I gathered by observation and guesswork.)

He took the job. He brought home a yearbook from the institution, and I looked at the senior class of nine high school students that I was now destined to join. I cried, I was angry, I’m sure I wanted to say “You can’t do this to me!” but I think I didn’t say it out loud. From Morningside High School to Columbia Christian would be like regressing decades in time. These nine kids looked like the Nerds Club to me. What a horrible fate I felt I was facing.

We started packing. There were boxes in the hall. Momma and Daddy decided it would be a good idea to take a quick weekend trip to Nashville to see all the relatives, since they knew it would be quite awhile before their responsibilities would allow that kind of break again. They were there for a long weekend, and reported that Momma had spent the night alone with Grandmommie, Daddy had spent the night alone with Nannie, all the aunts and uncles had been seen, and it had been a good visit.

While they were in Nashville there was another Campus Evangelism Seminar, this one held at UCLA. By this time, the leaders of Campus Evangelism had come to realize that the young adults they were trying to inspire to take their faith to the nations really didn’t have much of a personal experience with Jesus. They changed the emphasis of Campus Evangelism from outreach to inreach. Instead of talking evangelism, they began confronting the college kids with their need for a personal commitment to Jesus as their Lord. I had made that life-changing decision at the seminar in Dallas the Christmas before, so this seminar I knew there would be some kind of experience that would be personal, for me, rather than a challenge to perform in some scary, evangelistic way.

One afternoon, the speaker told us to all find a quiet place, alone, and spend some time with God before we returned to our small groups. I wasn’t really comfortable spending time alone with myself, much less God, so I took myself to the room where our small group would convene later. I sat and opened my Bible, and some verses jumped out at me. I knew God was speaking to me, and some of the words made that all the more obvious.

I had never read the book of Lamentations before, so these verses in chapter three were brand new to me. This is the King James Authorized Version; it’s probably the version I read that day:

It is of the LORD’S mercies that we are not consumed, because his compassions fail not.

They are new every morning: great is thy faithfulness.

The LORD is my portion, saith my soul; therefore will I hope in him.

The LORD is good unto them that wait for him, to the soul that seeketh him.

It is good that a man should both hope and quietly wait for the salvation of the LORD.

It is good for a man that he bear the yoke in his youth.

He sitteth alone and keepeth silence, because he hath borne it upon him.

He putteth his mouth in the dust; if so be there may be hope.

He giveth his cheek to him that smiteth him: he is filled full with reproach.

For the Lord will not cast off for ever:

But though he cause grief, yet will he have compassion according to the multitude of his mercies.

For he doth not afflict willingly nor grieve the children of men.

Especially because of the mention of youth in verse 27, I really felt this was God’s voice speaking to me. I didn’t know there was anything like that in the Bible, that said it was God’s love for me that had brought my suffering, and that it was good for me, not destructive. I don’t think I had been aware before that God could to speak personally to an individual through scripture.

When the small group started to gather in the room where I was sitting, the leader asked if anyone had something to share from their time alone, and one of the college girls read aloud the exact same passage I had just read. That freaked me out, because it felt like God knew I was a little shaky on whether this had actually, in fact, happened to me, and He wanted to confirm it, verse for verse.

This weekend was also the first time a strange guy had approached me, or “hit on me” as we say these days. An Indian man, a student at UCLA, engaged me in conversation and made me really nervous when he asked for my phone number and wanted to get together again. Although he was earnest and seemed really kind, I was not prepared to be asked out by a college guy, especially one that no one knew. But there was some personal attention there that I think God intended as a blessing. I was too scared to accept it.

The Monday after the seminar, we girls went to the beach, and I think the cleaning lady who was at the house that day felt I was being irresponsible, because my dad was sick in bed. He had come home from the Nashville trip feeling bad. But Daddy told me to go ahead and have fun at the beach. The next day he went to the doctor. Dr. Allen was out of town, and his junior partner told Daddy he had the flu and sent him home.

We discovered later that this same young doctor had sent about a hundred students home with a diagnosis of mono, when in fact only a handful of them actually had it. I could have become bitter about this lapse in medical expertise, and railed against circumstances as the cause of Daddy’s death. But the experience with scripture that weekend made me feel strongly that God knew this was coming, and that its timing was right, and no accident.

On Wednesday morning, Daddy called me into the bedroom and asked me to rub his back. I found out that he had spent part of the night on the kitchen floor, his back had hurt so bad. After I rubbed it for awhile, he sent me to my room to get dressed for work. (That summer I was starting to volunteer in the business office at Pepperdine, to get some secretarial experience.)

I was standing in my closet when I heard a strange sound from his bedroom, and ran in there to see what it was. He had fallen across the bed, on his back, and he wasn’t breathing. His face was already a little bit gray. I ran to the stairs and called to Mom to hurry upstairs, but she was eating breakfast and was not in the mood to hurry. Finally she came, and she told me to run and get our neighbors the Kinneys. We had never faced a health crisis before, and we were not being very logical. I should have, could have called 9-1-1 the first minute, but I’m not even sure 9-1-1 existed in 1969. On the other hand, Mom’s belief system said, “Most illness is in your imagination, you’re not really sick, get over it and get on with it,” so she was just acting like herself. (For instance, she didn’t believe there was any such thing as allergies. That was just people being silly.)

As I banged on their door, I cried a tear or two of panic, but then Jim and Dave came with me next door. They could see the reality of the situation, but Momma and I couldn’t. I had CPR in school that year, so I decided to try mouth to mouth resuscitation. (At least five minutes had passed by now, but I was ignorant about what that would mean, and also too panicked to think straight.) The mouth to mouth didn’t do any good, and then the paramedics arrived and carried Daddy off to Daniel Freeman Hospital.

As we sat in an examination room waiting for any news, a doctor came in and told us that he was gone. Mom cried out, “No, no, no, no…” and I sat there stunned and in shock. I stayed that way for a long time, and a deep part of me stayed there for years. It seemed to take no time for Pepperdine people to start arriving at the hospital. Bill Banowsky, then President (Norvel had become the Chancellor) came and he drove Sara and me back to the Gray House. He talked very kindly to me about my dad, and I have always appreciated the tender heart he revealed at that moment. When we got home, my mom sat on the couch in the living room, surrounded by Pepperdine ladies.

I was so grateful for her sake that she had that support, but she and I never did spend time alone or talk about any of it, so I felt very cut off from any grieving we could have helped each other do. Sara and Marilyn and Janice all were there, and we stood in the kitchen talking about it. Janice’s eyes filled with tears, and I thought how wonderful it must be to be so emotionally responsive. I envied her, because I was already shut down. And I was blessed that she allowed my situation to touch her heart.

Stephen Bennett came, and he drove us girls out to the beach for something to do. It was getting to be sunset on the way out, and I had quite a transcendent experience in the midst of the most glorious, flamboyant, sky-filling, orange and pink sunset amid mountains of luxuriant clouds I have ever seen, thinking about heaven, eternal life, and God’s love for Daddy and for me.

That night, we had planned to attend somebody’s wedding at Crenshaw Christian Church, and Momma said we should go on ahead. As I sat in the pew and watched the wedding proceed, I thought to myself, “My daddy won’t ever walk me down the aisle.” That became a verse in a song I wrote about fifteen years later.

“Just about to turn sixteen, lots of fears and dreams,

Momma said she was afraid I was running to free.

You left without saying goodbye, and that very night,

I watched a bride walk down that aisle where

I knew someday I’d be crying:

‘Daddy I miss you tonight, come and stand by my side;

Tell me it’s gonna be all right.’”

The morning after Daddy died, I woke up and instantly thought, “None of that yesterday really happened. It was all a bad dream.” But when I got up, I knew I had to face this terrible new reality. Daddy’s brothers, Paul and Winston, arrived from Nashville just to be with us and to help Momma make decisions. Chip and Sharyn, who were working with the Peace Corps in Lahad Datu, Malaysia, were somehow able to fly back to the States in time to attend the funeral in Nashville.

Daddy had talked about buying burial plots at Forest Lawn in West Hollywood, but he never had gone through with it. (One night in a dinner conversation with friends, I begged him to shut up about it, that it was a morbid subject. But he always said he knew he would die young. How I hated to hear that!) So Momma made the quick decision to use a vault in the mausoleum at Woodlawn in Nashville that Paul and Marian owned, and we flew there the next day.

The funeral was at the Hillsboro Church of Christ, and of course hundreds of people who had known both sides of my family attended. Most of the Nashville trip is a blur to me, but I still can see Momma and me sitting in the back seat being driven from the church to the Woodlawn cemetery, and thinking, “How can life possibly be going on as usual for everybody else? All these people are driving around as if nothing has changed. Don’t they know that the world has stopped? Can’t they tell they should stop too?”

I mentioned that we had been leasing family cars from the Buick dealership that rented its lot from Pepperdine. When we thought we were moving to Portland, Oregon, Daddy decided that we needed to buy a family car that would in some way make the move easier for me. He actually demonstrated that he understood about being a teenager when he brought home a bright yellow Camaro with a black roof. Wow! I was going to be allowed to drive this car! It was just weeks before he died. I found out that Daddy had bought life insurance that would pay off all debts on the insured’s demise, and that meant the Camaro was now paid for. The next year, when I started college, Momma got her own car and the Camaro became mine. What a gift that was from my dad.

Now that he was gone, there was no more moving to Columbia in Portland. There was no more threat of upheaval. Momma kept working at the library, I kept going to Morningside High School, Chip and Sharyn returned to their Peace Corps work in Lahad Datu, Malaysia. Pepperdine was still Pepperdine. We still lived in the Gray House on Crenshaw.

As I reflected on Daddy’s death, three things occurred to me. I was glad he was finally relieved of all the pain and distress and confusion that the ‘Sixties had caused him. (He despised and feared everything about that decade. That plus California had constantly offended his antebellum Southern gentleman heart.) I was glad he had finally finished his Master’s degree, after so many years of working on it. And, as I watched Hogan’s Heroes one night, as we had done together so many times, I wondered: If he had it to do over again, knowing what he knows now, would he watch TV or would he consider that a waste of time? I watched a lot of TV as a high school student, in addition to all my reading. I didn’t have too much social interaction in the after school hours, except for phone calls.

One conversation with Momma amazes me, because it indicates to me that I had more emotional wisdom at sixteen than I did in my thirties…or possibly more wisdom toward my mom than in regard to other people. She would come home from work and we would sit at the same supper table where just a few years before Daddy and Chip had also sat. Now it was just the two of us. We had shared a stormy, embattled relationship all my life, and now there was no buffer between us. Not that there ever really had been.

She began to confide in me the events of the day, just as she had with Daddy, except that their conversations had always been later in the evening after they had gone to bed. I wasn’t comfortable with these conversations, and I said to her one night, “You know, Momma, I can’t be your substitute spouse. I can’t be your advisor. You need to find somebody besides me to confide in.” How on earth did I know that? Thank God, I did.

Sometime pretty soon after Daddy’s death, the Dean of Women and the Dean of Students at Pepperdine took me out to lunch to counsel with me. Lucille Todd and Jennings Davis had watched me grow up and they wanted me to know that they would be there for me. I have no recollection of what they said to me. I certainly wasn’t bold enough to seek them out for help, so their objective ultimately failed. But I did appreciate that they took me to my favorite restaurant, Tai Ping, and I did understand that they were trying to reach out to me.

Something happened with Momma that was unsettling for me. Ann King, the widow lady who was dorm mother to Pepperdine’s girls, came over and took up the hems on all of Momma’s dresses, assuring her that she had a lot of years yet to live and should make the best of them. And Momma cut her hair. All the years of their marriage, she had worn her hair in a French roll, and now she went to the beauty parlor once a week and had it “done”. (Here she is with her new short hair-do, with the card catalogs in her library.) She did actually try going to a Christian singles’ event one night, but the next day told me about it as if she were a pre-pubescent girl who didn’t like boys yet and thought they were “creepy”. She didn’t try that again.

Something happened with Momma that was unsettling for me. Ann King, the widow lady who was dorm mother to Pepperdine’s girls, came over and took up the hems on all of Momma’s dresses, assuring her that she had a lot of years yet to live and should make the best of them. And Momma cut her hair. All the years of their marriage, she had worn her hair in a French roll, and now she went to the beauty parlor once a week and had it “done”. (Here she is with her new short hair-do, with the card catalogs in her library.) She did actually try going to a Christian singles’ event one night, but the next day told me about it as if she were a pre-pubescent girl who didn’t like boys yet and thought they were “creepy”. She didn’t try that again.Another scary moment occurred in the Gray House, although not nearly so invasive as the break-in. In the middle of night, Momma and I both woke up because a woman was screaming and a man yelling out by the curb on Crenshaw. They had gotten out of their car which was parked alongside our property, and she was trying to get away from him. Both of us went downstairs to be closer to the action and listen and see if we should do anything.

I decided to call the police and by the time the patrol car did arrive, of course the man had managed to get the woman back into the car and all appeared to be quiet. I was so mad! I knew the trouble would start again as soon as the police drove away. What could I do for her? I hated that we had to witness her being terrified and couldn’t help. I was right. When the police car pulled off, she tried to get away from the guy again, but he threw her back into the car and drove away.

In the summer of 1970, Grandmother Mattox died. Her funeral was in Oklahoma City, and Momma let me fly there with the Youngs because Sara and I were going on to Nashville to take care of Dad Young (Norvel’s father). I expressed some hesitation about being the only non-family member in the entourage and Matt said, “You can be my wife.” My sixteen year old heart was thrilled.

I was also thrilled that I was able to hear people talk about Irene Mattox and her wonderful life. Bill Banowsky, the young man that Norvel was mentoring, spoke about how Irene had written often to him, and to many other young preachers around the country, with encouragement and lists of books they should be reading. He said, “Mrs. Mattox proved an eighty year old can be more alive than most kids.”

Another man who spoke had been a teacher of Irene’s, and later of Emily’s when she attended Lubbock Christian College. His name was K. C. Moser. This was a man who was well known for teaching from the book of Romans about the grace of God. He got up to speak and all he said was, “Irene was a sinner, and she knew it. And Irene was saved by grace, and she knew it. And that’s all you need to know.” And he sat down. It was the most effective eulogy I’ve ever heard.

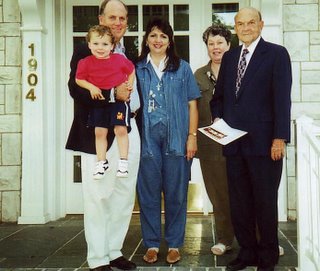

Sara and I flew on to Nashville, because we had been elected to stay with Dad Young. Whoever was looking after him needed a week or two off, and we were supposed to fill in as his caregivers. He was ninety years old, and still lived in the same house at 1904 Blakemore that Helen and Norvel had shared with him and Ruby while they were in graduate school at Vanderbilt, in the 1940s. Here's a picture of Stephen, Josiah and Marilyn Young Stewart, me, and Norvel in front of the Blakemore house, many years later. Norvel loved to drive by it often when he was in Nashville and reminisce about the years he lived there.

The old, two story house smelled of Dad Young's cigars, and also faintly of urine that had soaked into the floorboards over the years in the upstairs and downstairs bathrooms. It was hot and musty. He must have had no air conditioning upstairs, because we slept in a guest bedroom with the windows open. That was a summer of June bug infestation, and for some reason they wanted to harass Sara and me through the night. One night we had to sleep with the sheet over our heads because the June bugs kept dive bombing us. I really hate June bugs.

The old, two story house smelled of Dad Young's cigars, and also faintly of urine that had soaked into the floorboards over the years in the upstairs and downstairs bathrooms. It was hot and musty. He must have had no air conditioning upstairs, because we slept in a guest bedroom with the windows open. That was a summer of June bug infestation, and for some reason they wanted to harass Sara and me through the night. One night we had to sleep with the sheet over our heads because the June bugs kept dive bombing us. I really hate June bugs.We had fun, although it was a little scary, driving Dad Young’s car a couple of times, since both of us were just shy of sixteen, with only a learner’s permit. We had to go once to the airport, I can’t imagine why, and barely found our way home. Another time we drove Dad Young to B&W Cafeteria, which was in the Green Hills mall at the end where the Regal movie theater is now. Those were the days of Castner Knott and Cain-Sloan. Now in that same mall, it’s Princeton's Grill and Restoration Hardware instead. Dad Young loved liver and onions, so Sara and I went to the grocery store and bought some beef liver (gross!), pulled off the tough parts, floured it and dragged out the giant cast iron skillet to fry it in. We fried up some onions too, and it was actually not too bad.

We California girls were shocked at how early they rolled up the streets in Nashville. Because it was the Central time zone, the network TV shows came on there an hour earlier than we were used to. Johnny Carson was over too early to suit us, and there was nothing interesting on afterward. In fact, I believe the station played the national anthem and went to a test pattern. We were not good at entertaining ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment