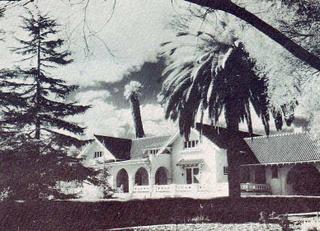

I’ve talked a bit about the Pepperdine campus, but it’s hard to communicate what it felt like to come to know a place so well. I loved having the feeling that this was my place, that I could wander wherever I wanted to and I belonged there. There was such a broad expanse of grass, with buildings all around the periphery. In the spring, that grass would be covered with little white daisies with yellow centers, and I would sit in the middle of the campus and play with them, and make daisy chains. To my dad, they weren’t daisies, they were weeds, and at least one spring I cried when he had the mowers cut them all down. How could he be so heartless?

The jacaranda trees that Daddy had planted along the sidewalk on the 79th Street side of the campus would bloom every year, making a purple haze, and the enormous date palms would actually flower and produce inedible orange-brown dates. There was another tree that produced pretty white flowers, and if you broke a twig off it there was a milky white liquid. We were told that tree was poisonous, and I think the juicy purple berries that the mulberry bushes dropped were supposed to be poisonous too. Giant eucalyptus trees trailed their rustling leaves beside the Fine Arts Building, and made mysterious shadows at night.

The girls and I felt we owned the campus, since we had the run of it, and one of the many signs of our passage there was a path in the grass from the library to the palm tree across from the cafeteria. That was “our shortcut” because we could push through a little hole in the bushes next to the palm tree. We knew we had truly made our mark when a few years later they gave up and just paved that diagonal brown line from the library to the palm tree where we had killed the grass, making it an official walkway.

Since all of the workmen at Pepperdine worked for my dad, I got to know many of them. Daddy taught us that everyone was worthy of respect and kind treatment, no matter what sort of job they did. The two men that stand out are Charlie Lane and Jack von Bender. Charlie had a British accent and an affectionate way about him. He made his nightly reports in a beautiful calligraphic script in a red journal my dad kept in his office. Pepperdine was so small and things were so quiet that we actually had only one night watchman for all those years. At one point, Dad paid Chip to walk around Charlie’s beat each evening about dusk, and make sure all the doors were locked and the lights appropriately on or off as needed.

Jack von Bender always wore a blue jumpsuit and he was so tall and big that it felt like hugging a mountain when I would hug him. I felt so safe with him. He worked for Pepperdine for years, even when we moved to the Malibu campus, and on a visit back there after I had graduated, I ran into him one day. He was working by the Youngs’ swimming pool. I walked up to him and called his name and gave him a hug. He started to tell me some memory about my dad, and had to turn away because he didn’t want to cry in front of me. What a teddy bear, a lover of a guy, was Jack.

Once, before I had my driver’s permit, I was waiting for Momma and Daddy in the family Buick and I yielded to temptation and started the car. I actually put it in reverse and backed the car a bit, unaware that behind us there was a metal pole sticking up out of the ground about two feet. What on earth was that doing there? The rear bumper was now hooked over the offending protrusion. I panicked because there was no way out and I was going to be in big trouble when my parents came back. Like an angel, Jack showed up, saw my predicament and lifted the bumper up off the pole while I inched forward. I was so saved!

My mother became Head Librarian of Pepperdine Library when it was still just one campus with just one library. Her office was on the front left corner of the building. You would walk up a few curved steps to the double front doors, entering the large front room with the oak card catalogues and the front desk. It was also oak and instead of a right angle, where it turned was a curve. (All the buildings at Pepperdine had rounded corners instead of right angles. The architect was consistent in his style throughout the campus. It may have reflected some influence of Art Deco.) To the right was the entrance to the Reading Room, a huge room with high windows and built-in bookcases all around the room, and long library tables with heavy chairs. Swinging wooden double doors with windows in them made a quietly heavy sound as you opened them to enter the cavernous Reading Room.

To the left of the front desk was the door to my mother’s office. When she sat at her desk, she was facing you as you entered. There were windows on two sides that connected and curved around from behind her to her right. There was a big closet to her left, and some bookshelves, her big desk, and a couch. She was an early believer in power naps. At lunch time she could fall asleep for twenty minutes, wake herself up and be refreshed. Here's Momma in the lobby of her L.A. campus library around 1971.

After school, I would sometimes stop by to say hello, but she was seldom really free to stop for a minute and talk to me. Always busy, in the early days she had a student secretary I met many years later in Nashville. Barbara Bailey Frank declared that she remembered me as a brat, and I was not too surprised to hear it. I stayed frustrated by my folks’ lack of attention. Both worked so hard in their jobs and at home that they were exhausted and never seemed to have anything left over for me at the end of the day. Also, Sara and Marilyn and I developed a certain bravado, a lack of boundaries, and a critical mouth. We projected a veneer of confidence that a friend later told me made it appear to him that we were “stuck up”. I explained to him that the veneer was a mask for our actual shyness and insecurity.

Another benefit of living in an academic community is that other adults besides our parents took an interest in us kids from time to time. One significant adventure for me was when Gloria Sanders took me to see the movie version of South Pacific. She was the wife of my parents’ old friend J. P. Sanders and the mother of three boys, so maybe she thought it would be fun to do something with a little girl. I fell in love with Bali Hai. I loved all the intense green rainforest, I loved the waterfalls, and of course I loved the soft focus shots inside the bamboo house when Lt. Cable sang to Liat, “Younger than springtime are you…” Waterfalls have been my favorite part of nature ever since.

Hayley Mills was an adorable little blonde girl, the child of a British theater family, and in 1960 Walt Disney starred her in a movie called Pollyanna. I saw the movie, I read the book, and I decided that I wanted to be like Pollyanna. It made perfect sense to me. Here she was, alone in the world (her missionary parents had been killed) living with a cold, unaffectionate aunt, and facing a town full of bitter, harsh or otherwise difficult adults. And she won every one of them over with her perseverance, her good cheer, and most of all her “Glad Game”.

Pollyanna’s father had taught her that no matter what happens there’s always something to be glad about. She revolutionized the town with his philosophy. Well, who wouldn’t want such power to make their world a happier place? So I proceeded to make her my role model. It didn’t help that later on I was steeped in the Shirley Temple movies. There was a Shirley Temple Film Festival on TV for weeks, and I caught every one. From Shirley I learned to be a “little trouper”, always to act brave and resourceful and take care of myself. In the end, these role models proved not to be the best, but they did help me survive in my childhood world.  Everyone loved Hayley Mills so much that the following year she starred in The Parent Trap. It was the first time, I think, we had seen an actor play twins, and she was adorable again. This time, instead of the prim Victorian era, the story was set in the present day. She got to be a modern kid and even sang a little pop music. So this was the first album I ever bought for my own record collection. “Let’s get together, yeah, yeah, yeah…We can have a lot of fun…” Pretty innocuous lyrics…yet I wonder, could this have been the source of the Beatles’ famous “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah…” from their hit “She Loves You” released two years later? I’m no musicologist; just wondering.

Everyone loved Hayley Mills so much that the following year she starred in The Parent Trap. It was the first time, I think, we had seen an actor play twins, and she was adorable again. This time, instead of the prim Victorian era, the story was set in the present day. She got to be a modern kid and even sang a little pop music. So this was the first album I ever bought for my own record collection. “Let’s get together, yeah, yeah, yeah…We can have a lot of fun…” Pretty innocuous lyrics…yet I wonder, could this have been the source of the Beatles’ famous “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah…” from their hit “She Loves You” released two years later? I’m no musicologist; just wondering.

As powerful as movies were to shape my life, I also learned that they were powerful to upset it. For someone’s birthday all of us little girls were taken to see Charade with Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn. I believe I asked an adult to take me out of the movie, because it was scaring me so much, but they probably felt they couldn’t do that and chaperone the other girls as well. At any rate, I dreamed about the faces of the several murdered people in that movie for some time after that experience. It took me quite awhile to learn that I was more sensitive than many people to visual images. It was years before I learned that I needed to take responsibility for what entered my mind. One day I suddenly realized that it was crazy to take in horrible images and then later have to ask God to help me deal with them. Why not just guard against taking them in at all?

Second grade was hard for me. I had an Asian teacher. I would have called her Oriental at the time, not being able yet to distinguish Japanese from Korean from Chinese. She was very strict, and I felt that she didn’t like me. I don’t remember what I did wrong, but as a punishment once she had me sit on the floor under the blackboard and she cleaned the erasers over my head by banging them on the chalkboard.

I never heard my parents discuss it, but they made the decision to remove me from Raymond Avenue and enroll me in the Lockhaven Christian School, where Matt, Sara and Marilyn went. One afternoon I got into the car and was told by my dad, “You won’t be coming back to this school.” I wondered if I had done something wrong enough to get me kicked out of Raymond Avenue. They never said what caused them to make the change.

My parents made another decision at that point which also helped to reinforce the direction of my early life. My reading ability was the only thing I knew of that made me stand out, but apparently they or someone believed that skipping a grade would benefit me. So now instead of being in third grade with Sara Young, I was skipped to fourth grade with Marilyn Young. Their brother Matt was in eighth grade, and before I was enrolled at Lockhaven I went with the Young family to attend a night time school performance in an outdoor amphitheater. Matt’s class was part of the program, singing, “Don’t Fence Me In”. That was my only contact with the school before I arrived. I thought that concert was pretty neat, so I might have been excited to go to school there.

My parents made another decision at that point which also helped to reinforce the direction of my early life. My reading ability was the only thing I knew of that made me stand out, but apparently they or someone believed that skipping a grade would benefit me. So now instead of being in third grade with Sara Young, I was skipped to fourth grade with Marilyn Young. Their brother Matt was in eighth grade, and before I was enrolled at Lockhaven I went with the Young family to attend a night time school performance in an outdoor amphitheater. Matt’s class was part of the program, singing, “Don’t Fence Me In”. That was my only contact with the school before I arrived. I thought that concert was pretty neat, so I might have been excited to go to school there.That summer between second grade and fourth grade, my parents tried to catch me up by hiring a high school girl from down the block to teach me cursive writing and my times tables. For many years, I explained my math blockage by the fact that I missed third grade math, joking that I was still insecure about the multiplication tables, but really it’s that I let my ninth grade math teacher make me believe I couldn’t do it. It turns out decades later that I have some aptitude for working with numbers after all. At the end of that summer, however, I did not feel ready for fourth grade.

This was the first time I had been driven to school. I would walk across the Pepperdine campus to the Youngs’ house and Helen Young would drive us to Lockhaven Christian School in Inglewood. I was scared at first, not knowing anyone in my class except Marilyn. Up until then, Sara and I had been somewhat closer since we were the same age, but now I would get to know Marilyn better. In fourth grade, at that young age, she was understandably not mature or thoughtful enough to try to include me with her friends, so I often felt alone at recess or at lunch. This was already my habit from previous years at school, and I didn’t know how to break out of it.

As in every group of kids, there were the cool ones and the not so cool. Cheryl Hall and her friend Mindy were always perfectly groomed, well dressed, quiet and nicely behaved. I felt like a misfit. My hair never seemed to do the right thing, my clothes never seemed to look right, and I didn’t feel very feminine. And I was too loud, too talkative, too opinionated and too passionate to be well-behaved.

Mrs. Feldkamp was my fourth grade teacher at Lockhaven. She was a perfect grandmotherly type, somewhat swishy in the way she walked, with an old lady voice. I remember her as very sweet. She had silver hair, and her hairdresser put a different rinse on it for each of the four seasons. It was green at Christmas time, violet in the spring, blue for summer, and I think somewhat golden for fall. I thought she liked me, and this was such a relief.

We were told to bring a set of colored pencils to school and keep them in our desks. I loved having my own desk, metal with a wooden top that lifted and my books and supplies inside. One afternoon each week, Mrs. Feldkamp would tell us to take out our colored pencils and draw, while she read aloud to us. She read an incredibly descriptive story about an impala (from the impala’s point of view) that made me fall in love with Africa, and she read us The Island of the Blue Dolphins. I so identified with that island girl, left alone to fend for herself. And I loved the colors of the colored pencils, and the feeling of creativity, letting the words of the story wash over me while I drew.

Which musical did the theater department at Pepperdine perform when I was in second grade? I don’t know, but I think Sara was in third grade (and Marilyn and I in fourth) when she won the part of Amaryllis in The Music Man. Once again, I fell into the role of coach instead of getting to be on stage myself. My mother played the piano and she was trying (with much resistance) to teach me, so I helped Sara memorize her piano piece for her role, the one Amaryllis called her “Cross-Hand Piece.”

I was jealous of Sara, because she was so cute and I was already gaining weight from my secret candy habit developed while waiting for the Brownie troupe meetings. Susan Teague, another faculty child, also got to be in The Music Man. She played the younger daughter of the Mayor and his wife, Eulalie Mackechnie Shinn. I consoled myself that Marilyn wasn’t in the play, just like me. That was the end of Marilyn’s and my careers in the theater, but Sara went on to play another part, one of the children of Job, in a play by Archibald MacLeish called J.B.. The star of that show, Mark York, paid attention to all of us but especially liked Sara and would walk her home from rehearsal at night. Talk about a romantic…this college guy saved the rose petals from the roses he would pick in the Youngs’ driveway as he walked her home. She was by that time, what, twelve years old? What a heartbreaker she was.

Now that I was in the same school with the Young girls, and riding there and back with them in a carpool, it was natural to spend more time with them, especially after school when I was already at their house. When you turned off 79th Street onto Budlong, their block, you passed the Pepperdine Gym, and then you came to a black iron fence with brick columns. It extended a long way, down the front of their main yard. Then you got to the black gates, which could be closed but never were. There were tall dark cypresses and big magnolia trees, and along the driveway were sculpted box hedges and rose bushes staked to poles like saplings. When we were little, a lot of the yard to the right side of the driveway was a fruit and vegetable garden, though later as Helen became increasingly busy with Pepperdine work, it was transformed into a rose garden.

Now that I was in the same school with the Young girls, and riding there and back with them in a carpool, it was natural to spend more time with them, especially after school when I was already at their house. When you turned off 79th Street onto Budlong, their block, you passed the Pepperdine Gym, and then you came to a black iron fence with brick columns. It extended a long way, down the front of their main yard. Then you got to the black gates, which could be closed but never were. There were tall dark cypresses and big magnolia trees, and along the driveway were sculpted box hedges and rose bushes staked to poles like saplings. When we were little, a lot of the yard to the right side of the driveway was a fruit and vegetable garden, though later as Helen became increasingly busy with Pepperdine work, it was transformed into a rose garden.There was a swing set there, when we were little, across from the side entrance to the house. Remember the Mary Martin play, Peter Pan? I loved a three-part round from that musical, “Tender Shepherd,” that the children sang before bed. I found it entrancing to hear the parts of the round cross each other and fit together. One day, as we were swinging on the swing set, I tried and tried to get Sara and Marilyn to memorize that round and sing it with me. I don’t recall getting much satisfaction from that effort.

We picked raspberries and boysenberries with Helen in that garden. Boysenberries were unique to California at that time, and I loved the boysenberry preserves at the Knott’s Berry Farm Steakhouse. I would always order beef stew, and for dessert I would have their rolls and boysenberry jam. Helen later said she got too busy and just let that garden die. I don’t know why the Pepperdine gardeners didn’t help take care of them. I guess someone thought that was the family’s job.

For a long time, there was a big parrot who lived in those trees and we would hear him calling now and then. And for awhile, somebody gave some peacocks to Pepperdine and they would strut around the yard. (I wonder who fed the peacocks?) I also remember mourning doves who lived under the eaves of the roof near Sara and Marilyn’s bedroom windows. They said they hated the sound of those birds cooing, but I thought they were neat. (That’s how we talked back then.) They appealed to my quickly developing sense of the romantic.

There was a fig tree in the back yard, and I thought it was special that the figs ripened just in time for the Christmas visit of Helen Young’s mother, Irene Mattox. Mrs. Mattox loved figs, and Helen was so delighted to be able to please her mother in that way. The giant avocado tree in the back yard was a blessing not only because of its avocados – it was also our fort. The branches came down almost to the ground all the way around the tree, except for an entrance (Did we create that?) but inside it was like a tall green room.

There were nights we had slumber parties under the tree . . . until we got scared and ran into the house. Once the Youngs bought a large tent to go camping with across the country. We used it for a slumber party in the back yard. I believe the story goes that Norvel and Helen had planned to take the kids and camp across the country, but Norvel was called away on some kind of Pepperdine business and Helen had to finish the trip as a single parent.

You could get to the terrace through several other doors, but we always used the sliding glass one in the breakfast room off the kitchen. Stepping down from the terrace, you came to a large square rose garden surrounded by box hedge. We didn’t spend much time in the side yard on the other side of the house, but the back yard held the tennis courts, and there was the college track beyond them.

Norvel and Helen were big on family exercise when the kids were little, which was a novel idea for me, and we sometimes played tennis together. They had actually played tennis on those very courts years before, when Helen was a senior at Pepperdine and Norvel a young history professor. Old Brother and Sister Baxter lived in the house at that time because they were then the college president and first lady. Now, here were Helen and Norvel, after thirteen years in Lubbock, back at Pepperdine living in that mansion and playing tennis with their four children and me, their self-proclaimed adopted child.

I can still remember the phone number for that house. Back then, instead of the first two numbers, people used a word that started with the letters that you see next to those number on the dial of the phone. The Youngs’ phone number was “PLeasant 3-4702”. (The way we would say it now is 753-4702.) I called that number a lot, so I guess it burned itself deep into my brain.

Marilyn lived upstairs with Sara, in a big, long L-shaped white room, with slanting ceilings, and Emily lived down the hall from them. There were also two huge attics upstairs. One we didn’t play in much, but the other was connected to the girls’ room and we played there a lot. We decided that one side of that attic was for Marilyn and the other side for Sara. (Or maybe a wise mother decided that so as to avoid arguments.)

I had learned about neatness and housecleaning at home, and somehow I decided that it was my job to be Sara and Marilyn’s maid. I straightened up their “playhouses” on either side of the attic many times. Other times I cleaned the kitchen downstairs without being asked. I think it was the first thing I did in hope that I might receive praise or notice, approval or acceptance.

One time we were giving a doll baby a bath, and when we were through, we poured the water through the floorboards. We didn’t give a thought to where the water might go. Years later, I believe it was my sixteenth birthday dinner, we were all sitting around the table in the beautiful, dark paneled dining room downstairs, and Helen said, “I always wondered where those water stains around the chandelier came from.” Marilyn and Sara and I all looked at each other wide-eyed and giggled. We suddenly realized what we had done! It took us a few more years before we were ready to confess it to Helen.

The girls were only seventeen months apart. Sara recently mentioned that their mom always dressed her in pink and Marilyn in blue. I always thought the color pink really suited Sara, and that Marilyn really was a blue person. I liked the color green the best. They fought like sisters often do, and once Marilyn got so mad at Sara that she threw an aspirin bottle at her and broke a shower door. Sara still has the scar on her shoulder where the broken shower glass cut her.

All three of us said and did things that hurt each other, but the two sisters actually competed a lot. I didn’t. I never had an urge to compete. Instead, my automatic reaction was always to default, give up, defer, give in. It took me years to learn why that was. And it took me a long time to learn that God had truly given me sisters in my relationship with Sara and Marilyn. Because they hurt my feelings sometimes, left me out of things sometimes, didn’t defend me sometimes, etc., I thought they didn’t really love me. But many years later, in one brief conversation, a lady named Mandy who had two sisters herself changed my perception. She helped me realize that we had acted just like sisters usually do, all those years ago.

o ~ o ~ o ~ o ~ 0

Time out for some family history. Why did the paths of the Youngs and the Moores so often cross? Norvel and my folks met in Nashville, Tennessee, where the three of them were in high school plays together. When Norvel Young was a teenager, he and my mother were good friends. She told me that he liked to try out new words on her -- big words, unusual words. I have a photograph of them going horseback riding together. My parents and Norvel attended high school and then college together at David Lipscomb (a two-year college at that time, later to become Lipscomb University) and then they all graduated from Vanderbilt University.

Then Norvel became a professor at George Pepperdine College, in Los Angeles. Pepperdine College was still relatively young at that time. It had been founded by the owner of Western Auto, and it was the main thing he had left when the Depression wiped out his fortune. Helen was a senior, and a student in Norvel’s class. She had grown up in Oklahoma City, but the Church of Christ circle was small enough that both Helen’s mother and Norvel’s mother were able to call friends to “check on” the possible coupling and see if it would be an acceptable and appropriate match. And it was.

Norvel and Helen got married and decided to move back to Nashville for awhile to go to graduate school. They lived with his parents at 1904 Blakemore Avenue. (Here is a picture of their daughter, Marilyn, her husband, Stephen Stewart, their son, Josiah, Norvel and me at the front door of that house.) They both went to Vanderbilt to graduate school, and Norvel’s mother taught Helen all the things that Ruby thought Helen needed to know about being a wife and running a household.

Then Norvel became the preacher for the Broadway Church of Christ in Lubbock, and that congregation funded my parents’ and several other missionaries’ efforts to do relief work in post-war Germany. They were the first American civilians to enter Germany following World War II. Because it was so difficult to get entry permits, they had to wait in Zurich, Switzerland for six months before they were allowed in. There, in the mountains outside Zurich, my folks and three-year-old Chip lived in a cabin in the woods where they carried water from a well and had no electricity. The story goes that they kept Chip close to the house by telling him that there were wild boars in the woods that would kill and eat him if he ventured too far. Once allowed into Germany, the missionaries distributed food and clothes to poor people.

Later on my dad designed and was contractor for the construction of several church buildings, often using materials from the bombed-out rubble. (Here's a photo of him conferring about the work, probably 1947.) In 1963 I was able to see for myself the beautiful pale blue and violet stained glass windows of the Senckenberg Anlage church in Frankfurt, and was told that those were created from broken glass that resulted from bombings. The missionary group started little congregations all around Germany. Helen and Norvel brought Mrs. Ruby Young on a trip to Europe, and they traveled with my parents for six weeks.

Later on my dad designed and was contractor for the construction of several church buildings, often using materials from the bombed-out rubble. (Here's a photo of him conferring about the work, probably 1947.) In 1963 I was able to see for myself the beautiful pale blue and violet stained glass windows of the Senckenberg Anlage church in Frankfurt, and was told that those were created from broken glass that resulted from bombings. The missionary group started little congregations all around Germany. Helen and Norvel brought Mrs. Ruby Young on a trip to Europe, and they traveled with my parents for six weeks.

Fast forward a few years, while the Youngs were still living in Lubbock, and our family was in Searcy. Pepperdine was in a terrible way financially, and Norvel was invited to move back to California, be its next President and reinvigorate it. After a year there, he called my dad and said, “J.C., I need you out here,” and we packed up to join them in salvaging a sinking college. They succeeded, to say the least. Pepperdine today is a thriving, nationally known institution, and it was Norvel and my dad who kept it afloat and began building its rich endowment.

No comments:

Post a Comment