Now, let’s yank ourselves back to the timeline. Fourth grade with Mrs. Feldkamp passed without too much trauma, but then came fifth grade and Miss Newman. Miss Newman’s stated personal goal was to see that each of her students was immersed in the waters of baptism before the school year was finished. She had a high respect for the Bible and one of her rules was that no other book should ever rest upon it. She would spot-check our desks periodically to see if there were any infractions.

The principal of Lockhaven was named Mr. McClendon, and his wife, “Mrs. Mac” also taught and worked in the office. Mrs. Mac taught us grammar in the old fashioned way that other kids our age weren’t learning, “parsing” or diagramming sentences. When I went to public school in eighth grade I found out none of my classmates knew as much about grammar as she had taught me.

Mr. Mac taught the old-fashioned way too, and he was especially proud of his eighth graders who could do math problems “in their heads.” He would take the best student around to the younger classes to quiz him in front of us and show him off. I was always scared of getting to eighth grade and being in Mr. Mac’s math class, and I was so relieved that I didn’t have to after all, because I switched schools again for eighth grade.

At Lockhaven Christian School we had chapel every day. That’s where the whole school came together in a church across the playground, and we sang songs and prayed and people would speak to us about God and the Bible. Once Mr. Mac spoke to the student body after we had a prayer. He pointed to a little boy, called his name, and said, “I want you all to be like this boy here. When it’s time to pray, he bows his head and folds his hands, and he shows his reverence for God.” I was afflicted with a long period of self-consciousness after hearing that instruction, hoping that anyone who looked at me while we were praying would think I was doing it right, and would admire my holiness. That self-consciousness was a hard habit to break in later years.

We also had a Bible class every day. I’m really glad I learned so much about God when I was little. It really made me want to get to know Him. I still remember some of the songs we sang at Lockhaven that I’ve never heard anywhere else. Here’s one I bet Sara and Marilyn remembered too:

“I’m so happy, and here’s the reason why:

Jesus took my burdens all away.

Now I’m singing as the days go by:

Jesus took my bur…He took my burdens all away.

Once my heart was heavy with a load of sin.

Jesus took my load, and gave me

wonderful peace within my heart,

and now I’m singing as the days go by:

Jesus took my burdens all away.”

I was now nine years old. Although this really-not-nice teacher named Miss Newman wanted every kid in her class to get baptized before the end of the year, I would not do it. I didn’t want to yield to Miss Newman’s pressure tactics. It was too important and personal a decision for me to do it out of fear or guilt. She tried to scare kids into believing they were facing the fires of hell if they didn’t get baptized. I wanted it to happen when I felt like it was the right time for me. I waited till the summer after sixth grade.

I guess it was around this time that we first heard about “the age of accountability”. We were informed that “the denominations” didn’t do baptism the way God wanted it done. They apparently had their theology all wrong. People who baptized babies didn’t understand that you had to make the decision to follow Jesus for yourself, as an adult. And they were hideously mistaken if they thought that God would send innocent little babies to hell because they hadn’t been baptized yet. See, there was an “age of innocence” and there was an “age of accountability,” and it was supposed that you made the move from one to the other sometime around the age of twelve. I had no idea of the theological, psychological and historical underpinnings of these arguments, I just knew that I wasn’t ready to make that decision yet. Somehow I trusted that God wouldn’t be mad at me if I waited until I knew I felt ready.

I think Miss Newman saw me as one of her less compliant students. Once I did or said something that brought on one of her famous paddlings. She was the only teacher at Lockhaven who had a large wooden paddle in the classroom, and she came halfway back in the classroom to where I was sitting, grabbed me up and smacked my bottom with her paddle. Unfortunately, the paddle broke and the class fell to laughing. I don’t remember being so much shamed by the laughter as I was angry that she hit me. Feeling not very ladylike or feminine, I was embarrassed by the teasing because I had broken her paddle. Miss Newman was not a happy person, and we were all so glad to be finished with her class.

Fifth grade did hold one bright memory. I already had several crushes on college guys. My first crush was on Terry Giboney, when I was about seven or eight, even though I knew that he was already taken by the lady he later married, Susan. This was the first time I had a crush on a boy my own age. Matthew Kauffman was the only non-Christian child at Lockhaven Christian School (as far as we knew). He was Jewish. What moved his parents to enroll him there, I can’t imagine, but there he was and I loved him. He was loud and brash and funny and free and intelligent, although I couldn’t have put that into words at the time, and he seemed to like me too. But we weren’t old enough to be talking about “boyfriends”. That came later, in sixth grade, with Raymond Pate.

In fifth grade, I also began inadvertently collecting friends whose names started with “B”. I’ve had a steady stream of friends with “B” names all my life. Barbara Markovich was such a good buddy at Lockhaven that she came with me on a trip up to our cabin in the mountains. My best friend in junior high was Beth Urban, then came best friend Barbara Rueckert in high school. In college I had two memorable roommates, Betty White and Barbara Henderson. My co-worker and friend in my first real job was Becky Batson. A roommate for a few years in Nashville was Bev Lunsford, and since 1989 my best friend has been Barbara Patt. It may be entirely devoid of meaning, but I find random stuff like that just fascinating.

I was sitting in the back seat of the car as we were traveling somewhere one night. My dad was driving, and he got my attention when he explained that we were going to move to Germany for four months. He told me that German children were very obedient. They were quiet, and respectful. I would have to change my behavior. My ways would not be acceptable in Germany. I was too loud, too wild, too disobedient, and too vocal in my objections when corrected. Being me just would not work where we were going.

My parents took me with them when we went to the travel agent’s office and discussed our trip. My dad revealed that he had been thinking about turning this into a trip around the world. Why not? It was only debt, and he had a good job and knew he could pay it off within two or three years. (I believe at this time he was making between nine and ten thousand dollars a year. Many years later, I saw a promissory note he wrote to Momma’s mother, who loaned them money to buy the Pink House.) It was a chance of a lifetime, and he decided that we would do it.

It sounded so romantic and very exotic to my nine-year-old ears. And it truly was. We would go to London, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen, on our way to Heidelberg, Germany. There we would live for fourth months. On our way home to America in December, we would come the other way around the world. We would stop in Athens, Cairo, all over Israel, then New Delhi, Bangkok, Tokyo and Honolulu. Amazingly, my parents knew missionaries in almost all of the cities on our trip back home, and we made advance plans to spend time with them in each place.

The summer between fifth and sixth grades, my folks got me a German tutor. I don’t remember who the teacher was, but well I remember how much I hated it! I resisted the effort, didn’t try hard to learn it, and felt like a failure. I didn’t understand what the tutor was trying to teach me. Years later I realized that I had not yet studied the parts of speech in English that she was trying to teach me in German, so of course I couldn’t comprehend her explanations.

From that time on I carried with me a belief that I was bad at languages, which much later I still suffered from when trying to learn Hebrew. Later, I discovered in my thirties that as I became emotionally freer, my German improved, even after all those years of not speaking it. I could converse more easily with German people a decade later than I could while I was studying and living there! What a mystifying and sometimes frustrating wonder are the workings of the human heart and mind.

So it was September, 1963 and I had just turned ten. Somebody gave me a red journal titled Travels Abroad which I wrote in sporadically. There’s a black and white photo of Mom and me standing with all the Nashville relatives at the old airport there, waiting to get on the plane to London. I wrote in my journal that when we went to visit Paul and Marian and the kids at the lake house, they made me sleep with Ronny, while Bonnie Kay slept with Suzanne. I didn’t feel good about that, but I wrote that Ronny was really sweet to me. I also wrote that I had to go in the lake in Suzanne’s swimsuit.

So it was September, 1963 and I had just turned ten. Somebody gave me a red journal titled Travels Abroad which I wrote in sporadically. There’s a black and white photo of Mom and me standing with all the Nashville relatives at the old airport there, waiting to get on the plane to London. I wrote in my journal that when we went to visit Paul and Marian and the kids at the lake house, they made me sleep with Ronny, while Bonnie Kay slept with Suzanne. I didn’t feel good about that, but I wrote that Ronny was really sweet to me. I also wrote that I had to go in the lake in Suzanne’s swimsuit.

(L>R) Nannie Moore with David Whitesell, Lois Whitesell, Dot Moore (Momma), Bonnie Whitesell, Marian Moore, Bonnie Kay Moore, me. In the middle front are Pamela and Wayne Whitesell.

It also made an impression on me that on the airplane to London, they asked everyone to raise their hand who was from Pepperdine. One guy said, “I’m from Harvard!” and the stewardess said, “That doesn’t count.” And all of us from Pepperdine received special menus. Yes, folks, in 1963 you were given a printed menu prior to dining with real silver and china on overseas flights. Compare that to today’s “bistro bags”!

Daddy joined us in London, but then he would be making a different trip. Norvel sent him to Ethiopia on his way to Heidelberg, trying to make a connection for the school with Emperor Haile Selassie. (He must have succeeded to some degree, because one of the Emperor’s daughters later attended Pepperdine as a student. She was a gorgeous and gentle girl.) Daddy gave me some Ethiopian coins to begin my collection when we met him again in Heidelberg.

Momma and I caught up with Daddy, the Pepperdine students and Howard and Maxine White in London. The Whites had known my parents back at Lipscomb in Nashville many years before, but I didn’t realize that at the time. In fact, I learned later that another Pepperdine faculty wife, Ann Frasier, and Maxine had been friends at Lipscomb as college girls. The Whites had two boys, Ashley and Elliott, and the boys were reading a book about the explorer Thor Heyerdahl and his craft, Kon Tiki, when I met them. They were younger than me, not to mention male, and we were all somewhat shy, so we didn’t really click.

We had a really bad time in the hotel room when we got to London. Momma threw a fit and told Daddy she hated our hotel, and if this was the way the whole trip was going to be, she didn’t know what she would do. I was so hurt for Daddy. He couldn’t fix anything. He didn’t know what to do when Momma got upset like that, and I didn’t know what to do to make things any better. My personal of that hotel is my first Schweppe’s Bitter Lemon. It was a shock at first but then I decided I liked it. Also it was the first time I had seen TV that was not American. We didn’t have one in our room; I had to go down to the lobby and watch it in a kind of parlor. The BBC seemed strange, and I missed my familiar shows.

London was exciting. We went through the Tower and saw the crown jewels. We went to the British Museum, the Tate Gallery, saw the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, Westminter Abbey (I wrote in my travel book that it was “a little dark and dingy”. I noted also that Dickens and Mary Queen of Scots were buried there.) We drove in a tour bus past the house where Charles Dickens lived. I had read A Christmas Carol in the thick pink clothbound collection of Christmas stories and poems that I still own. (I was always trying to talk my family into establishing some sort of Christmas tradition, like reading aloud together on Christmas Eve, but they weren’t having any of it.)

The next day we took a day trip up to Windsor Castle and Hampton Court. Sunday we went to the Wembley Station Church of Christ, taking my first trip on the Underground. After lunch, we went to the British Museum, and I wrote, “There are in the Museum:

1. The Magna Carta

2. The 500 clay Biblical tablets

3. Famous handwritings

4. Ancient books and manuscripts”

The next day, Monday, we went to Warwick Castle, Stratford-on-Avon, and Anne Hathaway’s cottage. I loved finally getting to see what a real thatched roof was like. I was impressed, everywhere we went, that all the suits of armor were so small. I was already an Anglophile at that young age. I didn’t know C. S. Lewis yet, but Robin Hood had a regular series on TV, and knights in shining armor were in my heart for sure, along with Peter Pan and lots of English fairy tales. I started a European charm bracelet, and for London Daddy bought me a silver “Bobby’s cap”. I was anticipating seeing Piccadilly Circus, and so disappointed to learn it was a traffic roundabout and not a real circus.

More strangeness. I wrote, “We went to a little place on the big street near the hotel and had breakfast. The rolls were hard, the butter sweet, and the marmalade bitter, but it was a typical Continental breakfast. I finally got used to it in Heidelberg.” Did you know that in 1963, two out of every ten English people lived in London? That’s what I wrote in my Travels Abroad journal.

Amsterdam didn’t make much of an impression on that visit, although I do still have a wooden shoe we must have bought there. I got a little silver “wooden shoe” for the charm bracelet. After we got settled in our hotel room, Momma and I went out walking, and I desperately wanted to buy some flowers from a street vendor. She, of course, insisted that would be a waste of money, because we would only be there a day or two. I thought she was just mean and terribly unromantic to deny me those flowers. We did take a canal ride and I noted that “there are four hundred bridges in Amsterdam.” What a statistician I was at ten! The next day I enjoyed the diamond cutting factory, and seeing the Rembrandts at the Rijksmuseum.

In Copenhagen, I saw Hans Christian Andersen’s "Little Mermaid" statue in the harbor, and that was the charm I bought for my bracelet. We were taken to Elsinore where the story of Hamlet was set, and the concept of the Roman vomitorium was explained by the guide. (The hall there was equipped with such a room off to the side.) Feasting to such excess that you had to vomit, and then going back for more, seemed pretty nutty to me, but apparently it was considered the duty of an appreciative guest. Apparently we missed running into Lyndon Johnson (there on a state visit) at one of our tourist stops. I naively wrote that we could have eaten lunch with him, but were too late.

From Copenhagen we flew to Frankfurt, and there Daddy rented a car and drove us to Heidelberg. In my journal I wrote that Daddy brought me a monkey rug from Ethiopia. It was exotic, but it stunk, and I think we finally disposed of it. We would be living for the next four months in a small hotel a block off the Hauptstraβe (main street) called the Goldene Rose. It was on a little side street called St. Annagasse. (I learned that

Straβe meant street and

Gasse meant side street or alleyway.) Momma and Daddy had their own room in a small hallway on the opposite side of the hotel from the majority of the students. Across the hall from them were two college students, George “The Captain” Cooper, and a nerd named Craig Athon. We three got to be friends.

To get to my hotel room, you continued down the hall, turned left, and there was my door on the left, next to the night clerk’s room. I found out later on that he got drunk occasionally, and those nights were somewhat scary, to hear him stumbling and banging down the hallway on the way to his room. I had never been around a drunk person before. Yes, I was just ten years old and living in a hotel, pretty much by myself. My room had its own sink, a small table and chair, and a bed. There was a tall, double window that opened into the room. Outside the window, a wide ledge served as my icebox. The view out my window was not exactly attractive. It was the internal courtyard of the hotel, and all you could see was other people’s windows.

The room was heated by its own little radiator which stood under the window. The traditional bedclothes were called a “Decke” which was an overstuffed featherbed encased in a sheet-like bag, something like a giant pillowcase, the German version of a what we now call a duvet. You stuffed the Decke inside the case and buttoned it in. The Decke led to a great deal of discomfort for me. The radiator would go on and off during the night. Since the fall weather quickly turned into a cold winter, I either froze or sweated, alternating, throughout the night. The Decke would get too hot, then I would throw it off and freeze, then put it back on, then the radiator would come on and the process would start all over again.

One night, Craig Athon was asked to baby-sit me, and he took me to the A&W restaurant where we had all eaten before. They had hamburgers there, not totally like American but close enough. Daddy had given him money to pay for dinner. As the two of us walked along the street in the dark, I felt really old to be out alone with a college guy like that. (My self-image was decidedly not that of a child with a babysitter.) We heard music on a radio or maybe coming from a record shop, some folk singers singing “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” As we crossed a street heading back to the Goldene Rose Hotel, a car nearly hit me, and Craig grabbed me and pulled me back. It felt really good to be rescued.

Another night, Chip was visiting, and George and Craig and Chip and I sat up late in their room, talking. There may have been another guy or two there as well. They called it a “bull session.” I felt so grown up to be allowed to participate. And I really was holding my own, doing more than just listening. Years later, I mentioned the memory to Chip and asked him what on earth I had been like at ten. Why would he give me St. Exupery’s The Little Prince for my birthday at the age of ten? Now I realized it was a philosophy book, not a children’s book. “You were a philosopher,” he said.

o ~ o ~ o ~ o ~ o

It’s July 17, 2005. Charles Osgood announced this morning on Sunday Morning that today is the fiftieth anniversary of the grand opening of the Disneyland theme park, so I was two when it opened. I could measure Disneyland’s history less egocentrically and say the first time I visited it, the park was three years old.

I called Chip today to check a couple of dates, and asked him if he had anything to add to this collection of fragments. He said, “You’re the only person I know who’s ever quoted me to myself. I could hardly say anything you wouldn’t remember. When I was twenty, you would say, ‘You told me when I was ten…’. It was amazing.”

I responded, “Well, that’s because you didn’t talk to me a lot. I admired you so much, it was easy to remember everything you said to me.” I asked him if my recollection was true about his gift of The Little Prince for my tenth birthday, and his calling me a philosopher. He confirmed it.

o ~ o ~ o ~ o ~ o

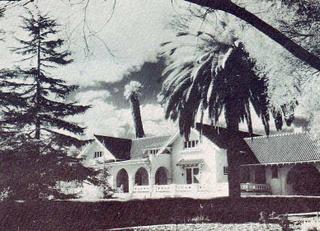

It’s revealing to look in my little red Travels Abroad journal and see what mattered to me as a ten year old. I don’t remember some of the names in the directory, which I carefully filled in so I could write people back at home from Germany. But I had been careful to get Mrs. Helen Pepperdine’s address before we left. That meant that old Mr. Pepperdine, the founder of the college had already died by the time I was ten. They lived at 1614 Wellington Road, and it was a gracious, old fashioned house. It reminded me of a home from another era, one that would have been approved by Emily Post. I can still see the upstairs hallway, the kitchen where Mrs. Pepperdine did so much baking, and the side room off the living room where Mr. Pepperdine’s hospital bed was when he was dying. We went to visit at least once when he was in that bed. There was a bluish light coming through a half-round window in that room, and he was so frail and weak. Above are pictures of George and Helen Pepperdine.

Now that we were settled in to the Goldene Rose Hotel, I was informed that I would be attending a German school. Did the teachers speak English? Not many of them, or anyway not that they were letting on. Did any of the students speak English? Yes, a few did. Two girls, Leslie and Lynn Haskins, were the daughters of the DubbleBubble manufacturing company representative for Germany. There was Madeline Wells and Cathy Leigh. A couple of the German students also spoke “ein bischen Englisch.” Other than that, I was up a creek when it came to communication.

The first day we visited the school, called the Englisches Institut, made a big impression on me. Momma and Daddy were taking me to enroll me and meet the Director, Herr Geske. We got me registered, and we were just in time to hear a brief concert by some of the kids. They gathered on a staircase and sang a couple of songs, in German of course. I was amazed at the purity of their voices, and their incredible diction. They were so good! I wished I could sing in a group like that. They were almost as good as the Vienna Choir Boys I had seen on Walt Disney’s Sunday night TV show.

Daddy had mercy on me and accompanied me to school each morning for the first week. I wrote that it cost “ten cents” – I don’t know if that was really ten cents or maybe ten pfennigs. We went on the trolley or street car (Straβenbahn) from the Hauptstraβe and there was one change, I believe, where I had to remember to get off and catch another trolley. When he felt relatively sure I wouldn’t get lost, I was on my own. So I went to class early each morning in the dark, and we stayed until five p.m. when it was turning dark in the evening. It was a long school day, especially since I didn’t comprehend much at all of what was being taught.

The first week when I went to the cafeteria for lunch, I was eating by myself and suddenly realized the whole room had gone quiet. Then I figured out that everybody was staring at me. What was going on? Somebody saw that I was confused and explained to me that everyone was laughing at the way I ate, using my fork in my right hand. The European way was to keep your knife in your right hand, and use your left hand to hold the food with the backside of the fork up to your mouth. This was much more efficient than the eternal picking up and laying down of utensils that the American way required, and I fell into that habit for several years.

Once in class, I was happily reading some English book I had brought with me to class, when again I realized that the atmosphere in the classroom had changed and I looked up. The teacher was standing at my desk and screaming at me in German. I truly didn’t understand what he was saying or what was wrong, but I figured it out that the teacher thought I should have been paying attention to class. It was pointless – I didn’t get most of what was being said, so I just read a lot. It was probably Herr Fischer, the math teacher. I wrote in my journal that he was “really mean.”

Of all the classes I had, the one I was able to do was “Diktation” where the teacher would speak German sentences relatively slowly and the class was supposed to write them down. This was an exercise in penmanship and spelling. I did pretty well at this, because my ear and spelling were both good, and I enjoyed learning the more square style of German penmanship, not rounded like the Parker method. This was the age when I began to be interested in calligraphy.

I made one good German girlfriend, Marion, who spoke a little English and was very merciful and kind to me. I didn’t like the two American sisters very much; they were too wild for me. They were already starting to be sexually active, telling me the facts of life one day in the bathroom (Unfortunate way to find out!) and having boys over for makeout parties when their parents weren’t home. I guess they were ten and twelve or so. They did keep me in DubbleBubble, though, and for that I was grateful They said they had a case of the bubblegum about four feet square at home.

After school, I would stop by the building where Pepperdine was holding its classes. It was called Amerika Haus, and was owned by an organization which offered lectures and other cultural events in English. It had an English library, even a children’s section. I would check out books all the time, as had been my habit at Pepperdine, and they were my companions through the long evenings in my hotel room. After my stop-off there, I would head back to the hotel and everyone would have supper together in the hotel dining room, the same place we shared breakfast in the morning. On Friday nights, it was a tradition that we would visit various other restaurants together, to get a broader experience of German and European cuisine.

Besides my library books, my other friend in my hotel room was a little radio. The Armed Forces Radio Network broadcast all over Europe, and I had the benefit of their English news, music and special programs. The broadcasters knew that American children across Europe needed English-speaking entertainment, so in the early evening they had story time. I could appreciate the old folks’ tales about the days before TV when everyone gathered around the radio, since for those four months the radio was my lifeline and companion.

Where were my parents? I had long since learned to entertain myself, so I’m not sure what they did in the evenings. I know they rarely shared them with me. We had a family story about their previous German period, how they left Chip one night in a hotel room and went out, only to return to find he had climbed out the window, and down a two-story pile of rubble, in order to play with some children he saw outside. My dad’s brother reported, after my parents were both dead, that when Chip was a baby, he and his wife would find Chip crawling in the driveway between their apartment and my parents’. He said this happened more than once, and shook his head. So I discovered that neglect was a pattern that was never named or addressed, but deeply felt by me.

German schools were different from American schools in many ways. When we entered the classroom, it was really cold! The windows were kept wide open, even in winter. Later I realized that perhaps one reason for that custom was the odor…all those kids, and no deodorant. The American habit of masking natural body odor had not yet caught on in Germany. Or maybe they couldn’t afford it. Anyhow, it was cold in the classroom, and discipline was rigid. When the teacher entered the room, all the kids rose, clicked their heels together and said in unison, “Guten Morgen, Herr Professor Schmidt” or whatever his name might be.

When it was time for what we called P.E. in the States, we didn’t put on the typical American gym clothes of shorts and shirts. Instead, we had to buy black leotards and body suits at the department store, and we looked like gymnasts or dancers in them. I didn’t like my chubby body being so exposed, but everybody had to wear the same thing. And in Biologie, the kids were more advanced than in my grade in America, and were already using microscopes and doing experiments and learning about Mendel and genetics.

For each class, you had to buy a separate little notebook. They were standardized and you could buy them at any stationery store. They were called a “Heft” and were really just a paper booklet stapled together. I learned about German precision and care, exemplified by the fact that they also sold thin little plastic slipcovers for your Hefts so they wouldn’t get messed up, torn, wrinkled or wet. I liked the graph paper Hefts the best. I started enjoying going into the German stationery stores just to look around and relish all the different kinds of paper and pens and pencils. My fascination with office supplies continues to this day.

So the weeks and months passed. I would write air letters, blue paper that was prepaid for Air Mail overseas postage and marked with where to fold and seal it so it was just one piece of paper. I learned to write very small so as to get as much as possible into an air letter. I got some letters from the grandmothers in Nashville and from my friends in L.A., but never enough. This was the first time mail was precious to me, and I appreciated so much being remembered by my friends in California. I really was afraid they would forget me and I wouldn’t have any friends at all when I got back.

In October we went to visit a German family, the Rudy Walzebrücks, in Stuttgart. The whole family spoke English, so I had a better time than usual. There were cute little blond girls, younger than me. We all helped fix lunch, and there was a giant pot of boiled potatoes that I helped to mash. It felt like a genuinely happy family, and I was enjoying being around them.

I was supposed to be taking a nap in the top bunk of the girls’ bedroom, but I had found a LIFE magazine in English so of course I was reading it instead. It had the most horrible article, a supposedly true account of a woman who had been stabbed in her own home, in the morning after her family had left for work and school. She had run to the neighbors, looking for someone to help her, but no one came outside, and she finally died. This article came complete with photographs, in that harsh, graphic photo-journalistic tradition, and it was more than I could handle. I was deeply scared by those images, for a long time. I couldn’t talk to my parents about this kind of thing. They just didn’t know how to do or say anything that might be comforting.

We had a fun trip to Switzerland. Momma and Daddy and Chip and I took a road trip with Snookie (Sara) Smith in a little light blue VW bug we borrowed from the White family. You counted four adults, so I’m sure you’re concerned about where I had to sit. My place was in the pocket behind the back seat, under the little oval window. I thought that was fun! In Interlochen we ate our first fondue. It seemed to me that Chip felt nervous and under pressure because Daddy wanted to be sure that we went to the same restaurant that Chip had visited when he worked for Russell and Doris Squires’ touring group. We went to Lucerne, where a swan followed me across the covered bridge on the lake. We saw the famous wounded lion carved into the stone wall over a pond there. We stayed in a fancy hotel in Bern, and I loved the luxuriousness, but I felt lonely in our room because everybody went out one evening and left me to read and go to sleep before they got back.

Now it was November, and our time in Germany would be over in just a month. My parents had gone out for the evening, to an opera. Daddy had given me a special treat, since I would be home alone for a long evening. He had bought a little plastic cup and bowl with some kind of cartoon character on them, and with them he brought me a box of corn pops and a bottle of milk. You could set a bottle of milk on the ledge outside my window and it would either freeze or stay cold enough to keep, so he thought I would enjoy having some cereal before I went to sleep. (Also in my Travels Abroad journal was a pressed flower from a violet plant that Daddy had bought me. It seems he had pity on my lonely state from time to time.)

I was sitting at my little desk, reading and listening to the Armed Forces Radio Network, when there came a sudden break-in announcement. I felt such shock when the speaker said, “President Kennedy has been shot. The President is dead in Dallas.” I had loved the Kennedys. I loved their youth and attractiveness. I loved seeing the LIFE Magazine photo spreads, black and whites of Jackie and Jack on the beach at Hyannisport, their children, the President in his rocking chair, John-John playing under his desk, all that stuff. It was the Cold War, life was scary, we did “drop and cover” drills at school and we thought the possibility of atomic bombs and invasion through Cuba was very scary. And now the whole world was shaking, and the President was dead. Anything could happen.

I was just a little girl. I needed grownups. I hurried down to the dining room to see if any students were down there. They were. Everybody was gathering there to listen to the radio together. That helped some, but I still wanted my Mommy and Daddy to hurry home. The Whites arrived back from the opera, explaining that some official at the theater had interrupted the performance to tell the Americans what had happened. He had released them to leave if they so desired. But my parents had not come back with the Whites.

When my mother and dad finally appeared in the doorway of the restaurant, an hour or two later, I ran up to them and probably grabbed them, though I can’t recall.

I said, “Why didn’t you come home when the Whites did?”

“We decided to stay and see the rest of the performance,” they said. “There wasn’t anything we could do about it, so we stayed until the opera was over.”

“But I needed you!” I cried. (Or did I really say it out loud? Was it my heart that was crying, with my mouth remaining silent? I can’t say for sure.)

I wanted to explain to them what a huge thing this was to me, how shaken I felt. My world felt like it was crumbling. But I was a child, we didn’t talk much anyhow, and we certainly never discussed emotions, so there’s no telling what I actually was able to verbalize, nor what they were able to understand. The end result was that I felt my parents were scoffing at my drama.

“Don’t be silly! What are you so upset about? There’s nothing we can do about it. It doesn’t concern us.”

Even though I was only ten years old, I had a growing consciousness of world events, of political changes, of the threat of war, of the impact of this moment on the world, and my concerns were highly dramatic, while their tendency was to block out anything that they felt didn’t directly affect their lives. I didn’t understand that at the time. I just felt alone, and I felt I was being mocked.

I went to my little room, and lay in bed most of that night tossing and turning, unable to sleep. It was so painful, knowing I could not go to them for comfort. I felt the world was scarier than it had been before that night. And at that, my world had never felt safe to me.

The next day continued to be hard. Once we showed up at school, the officials told the American kids they were permitted to return home. So I got on the streetcar to go back to the hotel. I kept watching as the scenery passed by the windows, and it didn’t look familiar. I finally figured out that in my haste or confusion, I had gotten on the wrong streetcar. It didn’t stop for a long, long time, and when I finally was able to get off and I tried to figure out how to get back home, I had to walk a long way. It was a gray day, with a biting wind, in late November, and I cried as I walked into the wind. I took refuge at Amerika Haus, checked out some more library books, and made my way back to the Goldene Rose.

So it was September, 1963 and I had just turned ten. Somebody gave me a red journal titled Travels Abroad which I wrote in sporadically. There’s a black and white photo of Mom and me standing with all the Nashville relatives at the old airport there, waiting to get on the plane to London. I wrote in my journal that when we went to visit Paul and Marian and the kids at the lake house, they made me sleep with Ronny, while Bonnie Kay slept with Suzanne. I didn’t feel good about that, but I wrote that Ronny was really sweet to me. I also wrote that I had to go in the lake in Suzanne’s swimsuit.

So it was September, 1963 and I had just turned ten. Somebody gave me a red journal titled Travels Abroad which I wrote in sporadically. There’s a black and white photo of Mom and me standing with all the Nashville relatives at the old airport there, waiting to get on the plane to London. I wrote in my journal that when we went to visit Paul and Marian and the kids at the lake house, they made me sleep with Ronny, while Bonnie Kay slept with Suzanne. I didn’t feel good about that, but I wrote that Ronny was really sweet to me. I also wrote that I had to go in the lake in Suzanne’s swimsuit. From Copenhagen we flew to Frankfurt, and there Daddy rented a car and drove us to Heidelberg. In my journal I wrote that Daddy brought me a monkey rug from Ethiopia. It was exotic, but it stunk, and I think we finally disposed of it. We would be living for the next four months in a small hotel a block off the Hauptstraβe (main street) called the Goldene Rose. It was on a little side street called St. Annagasse. (I learned that Straβe meant street and Gasse meant side street or alleyway.) Momma and Daddy had their own room in a small hallway on the opposite side of the hotel from the majority of the students. Across the hall from them were two college students, George “The Captain” Cooper, and a nerd named Craig Athon. We three got to be friends.

From Copenhagen we flew to Frankfurt, and there Daddy rented a car and drove us to Heidelberg. In my journal I wrote that Daddy brought me a monkey rug from Ethiopia. It was exotic, but it stunk, and I think we finally disposed of it. We would be living for the next four months in a small hotel a block off the Hauptstraβe (main street) called the Goldene Rose. It was on a little side street called St. Annagasse. (I learned that Straβe meant street and Gasse meant side street or alleyway.) Momma and Daddy had their own room in a small hallway on the opposite side of the hotel from the majority of the students. Across the hall from them were two college students, George “The Captain” Cooper, and a nerd named Craig Athon. We three got to be friends.

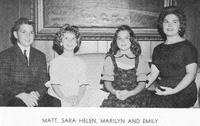

In the family room was Helen’s desk, near the side door, where she could often be found of a morning helping the girls make last-minute adjustments to their homework. There were also a couch, a TV and a stereo. We spent many, many hours there listening to music, playing records on that turntable. One of my happy memories of the family room was signing and addressing Christmas cards. All the kids, Emily, Matt, Marilyn, Sara and I were sitting with index cards in boxes and complaining about how many there were to do, and of course there was Christmas music playing on the stereo. Here's the picture of the kids that was inside that Christmas card. When she was little, they used to call Sara by her full name, Sara Helen.

In the family room was Helen’s desk, near the side door, where she could often be found of a morning helping the girls make last-minute adjustments to their homework. There were also a couch, a TV and a stereo. We spent many, many hours there listening to music, playing records on that turntable. One of my happy memories of the family room was signing and addressing Christmas cards. All the kids, Emily, Matt, Marilyn, Sara and I were sitting with index cards in boxes and complaining about how many there were to do, and of course there was Christmas music playing on the stereo. Here's the picture of the kids that was inside that Christmas card. When she was little, they used to call Sara by her full name, Sara Helen.