Since I had developed quite a taste for cleverness during my college years, I appreciated the witty bonnes mots being constantly dropped all around me. Other times, I enjoyed comments that seemed to crystallize a certain New England attitude, an upper crust mentality. Then there were those remarks that could be heard in any liberal theological institution – but only there. I captured a few of them for my later enjoyment.

Donald Moteka: “Ned celebrates the dull in life…the routine, the usual…”

Ed Boucher: “You know, there’s going to be a total eclipse of the moon tonight, and you can see it over Porter Hall, there in the east sky…” to which Michael Haggin replied, “Is this something you and Moteka whipped up?”

Carol Seifrit: “We got yelled at by the Rector for laughing at the bingo announcer – it was the Turkey Raffle –“ to which Michael retorted, “Don’t you know that’s the Eighth Sacrament?”

Carol, a Roman Catholic, liked to poke at my low-church Protestant leanings. She was dictating a quote to fill in a hole in my notes, “Among the marks of the True Church, the Petrine office…” and, noting my unconscious hesitation, exhorted, “Go ahead and write it, the paper won’t burn!”

Prof. Rowan Greer: “Oh dear, I’m sorry – I’ve confused Gregory the Wonder Worker with Gregory the Illuminator; the Armenians had nothing to do with this. Though they were next-door neighbors…”

Jill Bigwood, Registrar: (After punching in a remarkably long string of numbers on her office phone) “You dial this many numbers, you get God. Hello, God?”

Prof. Aidan Kavanagh: “…when we assemble to be most ourselves, in the act of Christian worship…”

Prof. Biddle: “I am offering this term ‘From Puritanism to Enlightenment’ – not an autobiographical course, by the way.”

One of my classmates signed her library card “Seven Promises.” We could hardly believe her parents had been hip enough to name her that. In actual fact, they were not. He knew I would love the irony, so Michael Haggin shared it with me, much to my delight. “You know, the one who taught meditation…She told us her real name. It’s Margaret Alice Wilcox.”

John Ferrie was horsing around: “I’m sure that in a former life, I was a scribe, and before that, J.” “Jay?” someone questioned. “J – as in J, E, P, D[i] – that’s me!”

Two guys who lived below me in Seabury were lunching one Saturday in the Refectory and I sat down with them. They were discussing a Christmas shopping expedition to the City. “You should have seen this sale…I was able to get two Persian rugs, since they were only $600 each. And a really nice diamond for my sister, not too large…” It was not that they were financially out of my league. I felt like they were from another universe entirely. So it was fun, listening in on their world.

Mike Johnston…the initiator of this adventure, and its primary focus… had gone missing. He was afraid, I guess, or I wasn’t who he thought I was, or he didn’t know what to do with me once he had me. Something caused him to choose the life of a hermit, just for that particular year. He claimed to have little or no time to hang out with me. It was my turn to learn to depend on God for my affirmation, to turn to God for any affection or understanding or compassion I might need. The words of a Lazarus song became even more precious to me, and I copied them into my journal, with no explanation, on January 19, 1976. I heard this Bill Hughes song now as coming from the Lord to me.

Memories can’t bring you home

Childish dreams make you roam

And there’s no time for guarantees

Of everything you are to Me

Let your eyes let you see

Let your ears let you hear harmony

Let your days let you be

Everything you are to Me

But there were moments of sweetness that the Lord provided, all surprises:

• Lanny Vincent and I walking arm in arm downtown

• Ed Boucher, entranced by Mahler and soprano Phylis Curtin

• Duncan Hanson taking me to see The Hiding Place and All the President’s Men

• Michael Haggin, affectionately holding my foot (!) one night as we talked

• Bailey from Georgia telling me, “Those were the best dances of my life!” after I dared a few rounds with him at a weekend dance in someone’s off-campus apartment.

• Phil McBrien and that great talk and walk after the B minor Mass performance, and a beer at Harry’s Bar

• Clifford Wünderlich, the Ugaritic scholar, with his “Yes, Ma’m”s and his always laughing at me, and his understanding, listening heart, and his confession to me, “I really liked Bernstein’s Mass – but I’m not sure whether it’s the Christian in me responding, or the pagan. I mean, I felt the same was at Carmina Burana – and that’s secular.” Mr. Wünderlich was also my informant regarding the arrival of Welch’s grape juice at the Eucharistic Table. “You know, Methodists used wine in the communion until Mr. Welch joined the church in the 1890s.”

I became friends with a young woman, Gretchen Law, who delighted and challenged me. She was an earnest person, very warm and bright, who confessed to me that she had never actually read the Bible. She explained that the reason she came to divinity school was that her adoptive dad had been healed of cancer, and she wanted to thank God with her life. I found this touching but also unbelievably foreign, being as I was a person raised on scripture practically from birth.

Gretchen was a feminist who was very comfortable with her body, and her unfettered freedom in that area sometimes made me nervous. She and a friend of hers, Linda Petrocelli, came to dinner one night while I was house sitting at the Worleys’. Linda shocked me by saying, “Gwen, you’re so much more comfortable with your faults that we are with ours. We find it difficult to talk about them.” She provided me with my first realization that everyone who loved God wasn’t necessarily prepared for my accustomed level of self-revelation.

Speaking of the Worleys, they were the couple whose apartment Mike and I had stayed in on my first visit to New Haven, Christmas, 1973. David and Melinda had since bought a house and had a baby girl. His family owned radio stations in Texas, and I believe they returned there after they both had finished their degrees. They were a very loving, welcoming, generous couple who loved to have people over for dinner, for Bible studies, to hang out.

The other married couple that was a huge blessing to me was Steve and Barbara Hays. They had migrated to Yale from Washington state carting loads of canned goods which had a prominent place on shelves in their living room. I felt like I was eating gold when they shared some of it with me. When I got sick at one point, they brought me food and Steve gave me a warm, padded winter jacket, which I lacked. They were most kind and hospitable to me, and together the two couples created a safe haven of family in my world of single oddness. Both couples were unreconstructed members of the Churches of Christ, though, so I was a bit of a misfit with them spiritually, having already partaken of so many non-C. of C. adventures.

Sue Wendorf was one of the handful of folks with whom I eventually had a few encouraging heart to hearts in those late evening dorm room visits. She shared with me a quote from her grandfather, a venerable old German Lutheran: “Was du nicht verstehen kann, mußt du glauben.” “What you cannot understand, you must believe.” This was the kind of thing one could say only late at night, in a whisper, to avoid being mocked by the less than pietistic.

I had a great time getting to know a friend of Mike Johnston’s, Dick Kantzer. Dick was the first true believer in biblical inerrancy I had ever met…at least the first intellectual one. I told him that I didn’t feel the need to claim for the Bible something that I don’t think it claims for itself. Dick was the most earnest, dedicated, kind hearted person, most intentional in the way he related to people. Sometime after we met, his father, Kenneth, became the editor of Christianity Today, and this was somewhat awesome to me as a longtime reader of the magazine. My parents had been subscribers.

Once Dick was house-sitting in the most marvelous old house in another town nearby, and Mike and I drove over to have dinner with him. I brought all the groceries and made my favorite, Senegalese Soup. I cooked a whole chicken to get the stock for the soup, and added peanut butter, applesauce, curry, sour cream. (See the Appendix for the recipe.) The main dish I had learned from Patrick’s mother the summer before, when we had spent so much time together at the Masons’ house in Nashville. She called it “What I Had in the House Chicken.” She said she invented it once for company on an instant’s notice: chicken breasts baked with mozzarella cheese slices, avocado slices and Liebfraumilch poured over it all.

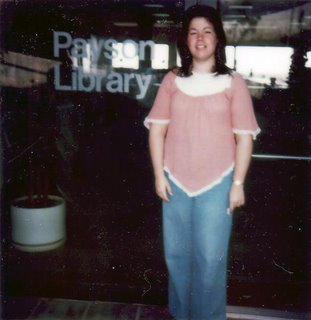

I went with someone to see the movie Clockwork Orange that spring. I don’t think I knew what to expect or I might have thought better of it. My confidence and security were already a bit precarious, and the weirdness of this movie threatened to push me too close to the edge. I ran into Dick the next day in the library and told him how freaked out I felt, and he was so helpful. He simply said, “Those kinds of movies can really change your consciousness temporarily,” and was so kind and tenderhearted about it that I felt drawn back to reality. One guy I became fascinated with but never engaged in a single conversation was from Iowa. He had graduated from St. Olaf, was studying to be a Lutheran pastor, and was looking like a combination of mountain man and angel. He had the Sam Jackson ruddy complexion and blond hair, a thick beard and a glow about him. When I read the definition of the Hebrew word “chen” I felt it was embodied in Thomas Schattauer: “pleasantness that radiates from the Giver, through the gifted, to a third person.” I knew where he habitually studied, in the Missions Reading Room (my favorite room too), and occasionally he was the last one I had to kick out as I locked up the library in my part-time job. By never speaking to him, I maintained the happy illusion that he was the dedicated, upright, morally true and brilliant fellow I hoped him to be.

And yes, there were a few moments with Mr. Johnston as well. As I recorded in a journal written about six years afterward, “Our last visit that year was the night before my last final in the spring. ‘You see what a terrible friend I am – I’m here tonight because it’s convenient for me, not for you,’ he said. He asked me what I had learned that year and together we made a six-point outline of issues (which I now long to remember, they were so perfectly clear) which YDS had raised for me and which I’d resolved in a Barthian dialectic. I told him how I’d failed him as a faithful friend (by desiring him as a romantic figure) and he told me about how he needed to study. I wrote a prayer about my relationship with Mike sometime that spring.

“Father, I want to talk to you about Mike. Here in the middle of my thoughts, in the middle of my life, I find myself, my heart, my days bound up mysteriously with his. I trust You that that’s because of Your plan for me, the ways You’ve arranged all the past, all the dreams, all the prayers. And he says to me, ‘It makes me wonder where we’ll be this time next year.’ And he says to me, ‘I need somebody who speaks my language; and you need somebody who speaks yours.’ ‘I’m sorry,’ he says. And for a moment my heart feels terror, fear at the prospect of not being really bound, bound and intertwined in time and space, with him here. But, Lord Jesus, when I sense myself asking to go on with him, I realize that more than that, I want him to go on with You. I rejoice and glory in the deeps, the purposes, the great still awe before You that I share with him. Tonight in this room there were moments when I felt him saying, ‘No. No, I won’t go with you, no, I’m not with you here.’ But there were moments when I sensed in deed we were here before You together. Even in writing, because of writing, and trying to capture, to keep, those moments, they lessen a little, they slip away. But the trust You create and sustain in my heart looks to You and not to him, and tonight it says, ‘Yes, You will go with him on that road, to a city far beyond the skies.’ That’s the glory and that’s the promise. I accept it as from Your hand. And if it means we’ll share all along the way . . . or if it means I’ll be watching and praying and believing all things, hoping all things, enduring all things, and not being able to see as I go — if it means I won’t live with him but only die to him, I give that to You back again — as praise.”

I wrote in a journal some years later, “Typical of the ambivalence of our relationship was my trip to Bev Nitscke’s ordination the next spring, when we discussed Biblical inerrancy and the critical method and he apologized that ‘You’ve come all the way up here to visit and we talk theology.’ At that point, that’s what I wanted.”

GottusoI didn’t start to journal my personal life until the fall of 1976, so I didn’t write anything about this experience at the time it happened. But I did write about it reflectively in a journal during the winter of 1979-80. “I hardly introduced this section adequately, given its length. I didn’t warn the reader, or myself, what I was up to. I’m doing my usual trick of the eternal preface. [It’s] a little jaunt down memory lane, an attempt to recreate for myself the images and memories which shaped who I have been and what the Lord is dealing with now. So now, if anyone besides myself ever shares this history, they’ll be prepared for a possibly lengthy continuation of this study. Let’s not hold our breath waiting for this part to end…”

Reid Rutherford, a friend I had made during my senior year at Malibu, was now living at home with his dad in Mendham, New Jersey, a place made famous in my life by its association with Camp Shiloh. I wrote, “My dear Reid had come once to New Haven for supper, to be a friend and also possibly to check out his heart toward me, as he was now a college graduate and still unmarried and here I was in the east…Well, it was reading week at YDS, the week before finals, and Reid was coming again to visit. Such a relief I was looking for –

“It had been four months since Nashville, since I had truly relaxed with anyone. The atmosphere at YDS was one of questioning rather than trusting, but I don’t believe I would have trusted anyone even if that had not been so. I was too careful to preserve my difference from that world, and too unsure of all that I was and wanted and could be. So many people there were types to me, proffering worlds which they represented and which I was invited to enter through them: Linda Mary and her Anglican milieu of a decadent tradition; Gretchen and her feminist/earth mother romantic/sensualist experience; Ed Boucher and his classicist apprehension of life; the preppy, intelligent-woman world of Carolyn Lyday; Bev Nitschke’s bracing, monastic, liturgical approach to faith.

“So I was looking forward to an easy, comfortable relief in the middle of reading week, with finals ahead and papers not yet begun. And Reid appeared – with two strange men in tow. It felt like an invasion, like betrayal. What did he think he was doing? I felt a great sense of violation. And it must have been a prescience of what was to come, because it was disproportionate. The last thing I thought I wanted that night was adventure or confrontation. I never would have guessed what was coming.

“I had been playing the guitar, so when they were sitting around my room, one of the strangers said, ‘Play for us.’ Well, I was being my hesitant, withdrawn Yalie self (which Lanny and others found so charming) and that was probably the seal on the direction of the evening. I asked innocently enough, ‘Who are you guys?’ and the older guy said, ‘Why do you ask that? Can’t you just be here with us and experience us without trying to box us into categories?’ Oh, please. I didn’t recognize the Zeitgeisty[ii] psychobabble and it was not a flow experience for me. So I got mad. I pressed the issue for quite awhile until finally one guy said, ‘I went to Pepperdine and I knew your dad.’ At that point, I had already left trust behind and I didn’t believe him.

“We went on like that most of the evening – the four of us went to a Chinese restaurant and John, the guy who swore he was friends with Daddy, ordered loudly and obnoxiously, and continued to bait my anger most of the night. We went for ice cream, and back to YDS, around the school and especially in the prayer chapel (where we sang in the dark). By midnight, something had happened – I couldn’t bear the idea of them leaving and me going back to my room and my books. There was something in me they were waking up and it didn’t want to go back to sleep. Yet it was scary. I knew I was on foreign soil, I didn’t speak the language and I was already meeting things in myself I didn’t know were there.

“So I asked if I could go back to New Jersey with them, to Mendham and Reid’s house. No definite plans, just ‘Take me with you.’ So we got in the car and started to drive. At that point I’d regained my distance and drawn back from the immediacy of these men enough to realize that the verbal confrontation guy, John Gottuso, had to be a shrink or related to Psych in some way. So the burden of my heart surfaced. I turned to him in the back seat, and said, ‘Can I ask you a question?’”

“I don’t know if I’ll have any answer, but you can ask.”

“What would you do if…if…you were dating a guy and…he decided to be…gay?”

“I had never experienced that being so hard to say before, and something broke in me – I started sobbing. Only once before had I let my heart feel Danny and the hurt and confusion of his gayness, and still it wasn’t in direct relation to me. Tom, a wonderfully ugly man who came to YDS by way of Shiloh and Nashville, was in love with a girl named Sam (who played Victory at Sea for me in her Wellesley apartment in Middletown). He and she were sitting in my room at Yale and he was talking about a part of his past when in Brooklyn and the ages of ten to twelve, he was a male prostitute. This conversation was only months after my two weeks with Patrick, and I wept in anger at Satan’s cruel destruction of sexuality.

“This time, for the first time, I was crying for me. Gottuso held my hand.

“Go ahead and talk about it,” he said, and I said, “No, I need to cry a minute, this is wonderful.”

So he got out his cotton handkerchief and handed it to me. (I hadn’t seen a man’s cotton handkerchief since I ironed my Daddy’s every summer growing up.) I don’t remember his saying anything really insightful or helpful (maybe I couldn’t hear it) but it was the first time I had trusted enough to unload my pain.

“When we got into Reid’s house, what seemed like mere moments later, Gottuso said, ‘Are you going to kiss me goodnight?’ So I did, on the cheek, and he said, ‘Why are you afraid of me? Why don’t you kiss me on the mouth? We do that in my family.’ I still don’t feel perfectly trusting of his motivations when he chooses to confront sexually. But that night I really didn’t trust – and it was myself I didn’t trust. Though I hadn’t awakened physically yet, I had confronted the reality of desire for the first time at YDS. One night I fantasized going downstairs and knocking on Phil McBrien’s door and saying, ‘Would you please just sleep with me? Just be with my body?’ So I was more aware than ever of my physical vulnerability, and it felt like it wouldn’t matter who or why.

“I stayed on through the next day and night and rode into the city Monday morning on the train with Reid. No other confrontation took place during the weekend. Reid may have felt some confusion or jealousy – we had a couple of talks, took a walk the second night out in the fields, but I wasn’t interested in him, I wanted Gottuso’s attention. I see it so clearly as a daddy transference now – that’s why it felt so wrong to kiss his mouth, and yet I did it the second night, on his prior dare.

“It felt very sensual to be in that house, partly because it held so many possibilities that YDS seemed to negate. That second night, Reid’s dad and Gottuso were conferring and I hung around to say goodnight and ask if I could come to see him in California that summer. He gave me his answering service, his unlisted number and his 24-hour emergency number, and now I knew he was somebody that did this for a living. He said he had been interested in seeing where I was, as a favor to my father.

“On the train riding into the city, Reid told me Gottuso had pastored the church he’d attended in L.A. and had helped him to change and discover a lot about himself. So then I figured maybe he was evaluating me as a favor to Reid. Whatever the reason, I’m convinced that I failed the mentally-healthy test as an entirely unawakened personality.

“But I’m also convinced it was the mercy of God coming to rescue me. I’d spent all my life not looking inside my own heart and for over a year I’d been trying to deal with another human being’s heart in a totally external way: seeing Danny as an innocent in the evil, cruel, deceptive clutches of gayness, rather than perceiving him as a whole person, sinning and responsible, yet growing, learning, possibly on the way to a real walk with the Lord rather than the false one he’d attempted. I still feel a lot of ambivalence about my view of him and what he’s in, but it’s so much broader and realer a view of life than the perception of externals only, where I was walking before. And I thought I understood, that I was so insightful regarding gayness before. I praise You, Lord, for Your faithfulness as a Teacher in this regard.

“Reid took me for a quick walk down the diamond brokerage block where he worked, and I saw my first Hasids in their black coats and side curls. Then he took me to Grand Central and stayed on the train until it was ready to go. I could sense, I thought, a certain hope, an attempt to test our possibilities and the accompanying disappointment when the magic didn’t happen.

“Back at YDS a few hours later (as always, it felt like pulling into the Heidelberg Bahnhof), the first person I saw was Michael Haggin. Already I was perceiving what had happened as transformative, because I told him, ‘Michael, you should be happy to hear this – I really want to go to a counselor now; I’ve started to wake up to some things.’ He, brave boy, was doing the quintessentially Right Thing by seeing a lady shrink, since he feels his problem is with women.”

Before I left New Haven for the summer, I had a little experience that more than made up for my initial harsh reception. I was walking, merely walking into a simple little corner market, mind you, and a white-haired man looked up at me from across some loaves of bread, and smiled and said, “You must have just about the nicest personality I’ve ever seen.” I said, “But wait, I just walked in, you never saw me before…” and he said, “I know, but I can tell. Where d’you live? I hope you stay here.”

I need to take a break from my journal and tell about an incredibly significant week that I didn’t cover therein. Toward the end of my year at Yale, the spring of 1976, I was becoming more comfortable with the idea of staying there for the three-year degree program. I had become so acclimated that I even toyed with idea of running for a student government office. But earlier, when I was still excruciatingly homesick for Nashville and the Christians there, I had prayed, “Lord, if You want me back in Nashville, here’s what I need. I need to be accepted as a transfer student at Vanderbilt Divinity School. I need a job where I can live, so that I can make money and not have to pay rent. I need that to be in walking distance of Vanderbilt and Belmont Church. If You do all that for me, I’ll know You want me to return to Nashville.”

Well. Behind the scenes, events began to conspire to make all of that happen. It seemed Naomi Frances Harper had found her a man. Greg Brooks, a gentle, quiet pre-med student, had asked her to marry him, and would I please come to Nashville and sing in their wedding? Of course I would. I arranged to spend a week in Nashville on my way back from New Haven to Malibu. I contacted Steve and Annie Chapman from Dogwood to see if they would play and sing with me, because at that point I had never accompanied myself in a solo performance and was too scared to do it. They agreed they would be glad to help me out.

When I arrived in Nashville, I discovered to my great anxiety that they couldn’t do it after all, and I really couldn’t see myself playing all alone. They suggested, “Call Bob Farnsworth.” “But I don’t even know him!” I countered. “That won’t matter to him, he’ll be glad to help.” They were right – this guy jumped like an eager puppy at the chance to accompany me, and we got together to rehearse. He played rambunctious piano, and we did songs by Annie Herring from the Second Chapter of Acts like “Bridegroom” and “I Fall in Love.”

“I fall in love so easy with everything that I see

that comes through the light of His love…

Sets my soul to flight, as He woos me and makes me new.

I hope you’re falling in love too,

‘cause Jesus loves you too…”

Bob was enthusiastic about my voice. He explained that he and his best friend, Mike Hudson, and Brown Bannister (I knew Brown from Janice’s wedding) were working in a jingle company with Chris Christian. I had heard about Chris from Janice as well. She had been amazed at his chutzpah when he arrived on a visit to California from Texas, expecting her to introduce him to various prominent people in L.A. But that was Chris… Bob explained that their jingle company wrote and recorded music for radio and TV commercials, and would I like to sing for them in the studio when I returned to Nashville in the fall?

Would I??! I would gladly pay them for the privilege. I could hardly believe such a thing was actually happening. At that moment I could never have imagined the musical experiences that lay ahead of me. I had come to Nashville originally to go to library school, not to pursue the music business. I didn’t even respect the music business in Nashville. I thought it was all country, and I hated country music, the sequin-spangled people like Porter Waggoner and Ray Stevens and such. I thought of it like John Sebastian’s song, “Nashville Cats”. (I won’t quote it – you can reference it elsewhere if you so choose. Certain readers will be grateful for this mercy, I’m sure.)

While I was there for the wedding, I thought I would pay a visit to Beckie King, one of Naomi’s roommates. She was the Director of a place called Hospital Hospitality House, and I went there to visit her. I let her know that I was thinking about coming back to Nashville in the fall, and she looked at me in amazement. “Would you be interested in a job?” she says, and my amazement matched hers. She offered me a position as a live-in staff member at the House, where I would be on duty some weekends and some week nights, in return for my room and board, whatever might be available through donations and their charge account at a nearby H.G. Hills Grocery.

Hospital Hospitality House was located at that time a mere one block over from the street Belmont Church was on, and about four blocks over from the street that ran through the Vanderbilt and Peabody campuses. I would be able to walk to church and school. I would have a job that paid my rent – and food, which I had not even prayed about. And I would be working in an environment where I would be of direct service to people in need, which appealed to me greatly. Just a stunning answer to prayer, and the opportunity to sing in the studio as well…now that was over the top. Needless to say, I accepted the job, and went directly over to the Divinity School to see what transfer arrangements could be made. They had no problem accepting a transfer from Yale.[i] The school known as “German higher criticism” used textual critical tools originally intended for the study of secular literature in an attempt to determine the sources of the Pentateuch in Old Testament scripture. “J” stood for “Yahwist” or those who called God by the name Yahweh; “P” stood for the school of priests, those concerned with ritual and practice in the Temple at Jerusalem; “D” was the Deuteronomists, or those concerned with the law; “E” I had forgotten and had to look up on the internet. It’s Elohist, or those who referred to God as Elohim rather than Yahweh. Then the theory goes that an editor, the Redactor, pulled these four sets of texts together into the five books of Moses, Genesis-Deuteronomy.

[ii] Zeitgeist = again, the spirit of the time; the spirit of the age. I made up the adjectival usage, “Zeitgeisty”.