Again, my parents decide to transfer me from one school to another without my understanding exactly why they did it. Lockhaven went through eighth grade, and I had fully expected to graduate from there and go on to high school somewhere. Instead, my folks told me I would be leaving seventh grade at Lockhaven and going to eighth grade at Airport Junior High. In one fell swoop, I left a school that spanned K-8 and had less than 300 kids total, where our class sat all day in one room, and entered a school of more than 3000, where each class was in a different building. And I knew absolutely no one there except our preacher’s son, Danny Teel. I didn’t really know him except from afar, since he was older, and since I had a minor crush on him.

Chip and Daddy took turns driving me to school that first week, and I cried in the car every morning. I just about begged Chip not to make me go. I was terrified of such a huge place. I didn’t know where anything was, and was too timid to ask anyone for help. I felt so shaky that more than once I sat in a bathroom stall and wept in the middle of the day. It was a big campus, and I had a long way to walk from some classes to others, plus a locker to keep up with. There was the problem of learning what to take with me from class to class, depending on how far they were from the locker. It was a complication I had not anticipated.

I’ll never forget the feeling of dread when I found out that we were required to take off all our clothes at our gym locker, and run naked to the showers at the other end of the huge room. Even then, the showers were not individual showers but large square areas with half-walls and ten or twelve shower stalls per enclosure, with dividers that only pretended to provide a tad of modesty. We were told that we would be required to stand there naked in the shower room, without holding up a towel for modesty, until the shower monitor has ascertained that we were actually wet and checked us off a list.

I sat on the gym floor after hearing these announcements and had another cry. I went to the gym teacher and asked, shaking, “What if it’s against my religion?” There were no excuses – unless you had your period, which I didn’t yet. If you had your period, you got to use a shower stall with a curtain. Some girls lied and said they needed to have a private shower when they really didn’t, but I never tried that. Later in life when I learned about Nazi Germany, I understood just a tiny bit the overwhelming shame and fear when the victims of the Holocaust were required to strip naked before their guards. I wondered if the girls’ gym teacher wasn’t a secret Nazi in her heart.

Airport Junior High had some bright moments, and some blessings, but it was mostly just hard. I rode the bus home from school. I was the only white kid on the bus, which taught me something about being a minority in a hostile environment. This was the ‘Sixties, and racial tensions were building in Los Angeles. In the summer after my eighth grade year, L.A. finally exploded into the Watts riots.

More than once I played hooky from school, I hated it so much. One time in particular, I plotted and planned so I could be sure I wouldn’t be caught. I actually hid in my brother’s bedroom until I was certain both Momma and Daddy had gone to work. I felt terribly sneaky and dishonest about it, and my conscience was pricked because I deceived them, but that feeling wasn’t as bad as my dread of going to school.

My parents couldn’t have imagined the environment at Airport Junior High, and I chose not to describe it to them. Kids my age were having sex (or at least boasting about it), smoking in the halls, having gang fights. It was reported that certain girls hid razor blades in the requisite six inches of ratted hair atop their heads, so that if another girl grabbed their hair in a fight, she would get cut. There was a knifing one afternoon after school.

We were approaching that age when little girls attempted to become young ladies. The school policy was that only girls in the second half of ninth grade were allowed to wear nylons to school. The rest of us were required to wear socks. To get around this, some of the rougher girls would wear hose under their socks, and the fashion among them was to see how many runs they could get in their hose and still wear them. This produced an especially dramatic effect when the hose were black or navy blue.

I had a few good friends who encouraged and uplifted me at that school, but I had another friendship which unfortunately introduced me to a different word. Helen was in my grade, but since I had skipped third grade I was a year younger than she. She was reading Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, and they were my introduction to the power of erotic literature. Of course by today’s standards the language and descriptions were tame, but I was stirred by them and knew instinctively without being told it was a guilty excitement. I was also fascinated with the Song of Solomon in the Bible, but its poetry was a bit beyond my ability to appreciate at that age.

I was escaping from this hostile world in books and in music. At some point, Pepperdine chose to put on another musical and this time it was Camelot. We girls already knew Mark York, because he had starred in J.B. and Sara had played one of his children. He would talk to all three of us like we were people, and I longed for his attention. In Camelot, he played the part of Pellinore, the bumbling comic character who was constantly on a Quest, and John Novak, Chris Stivers’ cousin, played King Arthur.

The most romantic character was, of course, Lancelot, and I had the inevitable crush on the student who played him. This guy produced my first real confrontation with the fact that giftedness – in this case, the ability to play a role – does not guarantee or even reflect genuine character. I heard that the young man who played the part of this ardent and awesome hero was in real life actually mean to his wife. This was a rude awakening. I’ve had to learn and re-learn that lesson many more times throughout the years, as it seems I tend to forget it.

Mark was talking to me after church one Wednesday night, and he said, “You’re too young to be a cynic. If you ever need to, I’d be glad to talk. I hate to see you heading in the direction you’re going; you’re too young.” That was sweet, but we never had those talks because I never asked for them. I didn’t trust that he meant what he said enough to follow through on the offer.

After I knew the musical note for note, Hollywood produced the movie version of Camelot, with Richard Harris, Vanessa Redgrave and Franco Nero. What a wonder! How excruciatingly romantic, particularly the montage of Ms. Redgrave so exquisitely portrayed in different seasons and settings as Lancelot sang “If ever I would leave you...” And Richard Harris, pondering late at night by a fire on the question of “How to handle a woman…Just love her, simply love her, merely love her.” My sensibilities were deeply influenced by the stage decoration of Arthur and Guinevere’s medieval bedroom.

The movie inspired me to read T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, a modern retelling of the Arthurian legend (based on Mallory’s L’Morte D’Arthur) which had been the source for the musical. I loved that book so much that I re-read it many times. I especially got into the chapters when Arthur was a young boy being trained by Merlin, and he gained rich insights by being turned into various animals. In my imagination I became that fish swimming in the river, along with Arthur.

We moved from the Pink House across the street from Pepperdine, way down 79th Street a few miles closer to the beach. Now we lived in a community called Inglewood, on Crenshaw Avenue, on an acre of land, in a big old two story Gray House. I had to walk a ways up a hill on Crenshaw from the bus stop, past some stores and apartment buildings, and a bakery I was usually but not always able to resist, on my way home after school.

We moved from the Pink House across the street from Pepperdine, way down 79th Street a few miles closer to the beach. Now we lived in a community called Inglewood, on Crenshaw Avenue, on an acre of land, in a big old two story Gray House. I had to walk a ways up a hill on Crenshaw from the bus stop, past some stores and apartment buildings, and a bakery I was usually but not always able to resist, on my way home after school.Daddy speculated that the Gray House had been a farmhouse on an estate that connected to the ranch presided over by the Youngs’ Spanish mansion. He thought our farm had probably run all the way to the ocean. Somehow, he talked the previous owners of the house into donating it to Pepperdine, which is why we were able to live there. Two other faculty families lived in houses on the same property, but ours was the main house. Helping with the move from the Pink House to the Gray House, I enjoyed the feeling of power I got in being Daddy’s “right hand man” lifting boxes, helping him carry furniture I should not have been carrying. We always had a working relationship, because I learned early on that was the only way to spend time with him.

Besides us in the Gray House, the Jim and Brownie Kinney family, old acquaintances from Nashville, moved in next door. Their three boys gave me personal attention without the competition of Sara and Marilyn. They played volleyball with me. Jim, the oldest, took me to the gym and showed me something about working out in the weight room, and they all took me to a concert for one birthday.

The Gray House was so pretty, and so conservatively decorated, that we didn’t do anything to change it when we moved in. Chip took the bedroom on the end upstairs, because it had its own little bathroom, and a private entrance with a staircase all the way to the ground, as well as a little office with windows on three sides, overlooking the patio below. I took the bedroom with yellow and white wallpaper, a room with windows on two sides with white shutters, and I had my own bathroom down the hall, across from the blue guest room where my old white canopy bed lived.

One night I stayed up late in the guest bedroom, because I was deep into reading Gone with the Wind. It was the only time I recall Momma having anything to say about my reading, and it made me feel good that she was thoughtful of my feelings. She advised me, “You don’t want to keep reading that tonight. If you try to finish it, you’ll be upset because it will be so late and it’s not a happy ending.” Even though I appreciated her advice, I ignored it, and I did finish in the wee hours, and she was right, I wasn’t happy about it.

Momma and Daddy’s room was pink, with its own bathroom, and it had white French doors that opened out to the flat roof that overlooked the patio below as well. You could sunbathe there, and my friends and I did that a few times. Their bed set into a small recess that jutted out over the yard, with shutters over the windows, and their brown furniture looked pretty there. Momma also found a pink velvet bench to sit at the foot of the bed, which I thought provided a very elegant touch.

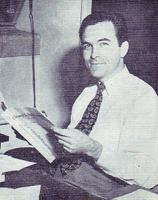

In the living room we had a “new” couch that Daddy had found in an estate sale. He had someone reupholster it in a light blue Chinese brocade. The seat cushions were stuffed with feathers, so in order to look right, they had to be fluffed. This meant that no one was allowed to sit on the couch except company, since Momma didn’t want to have to re-fluff them for just us. Recently I was watching a video of comedian Rita Rudner and was reminded of Momma. “We know that neurotics are those who build castles in the air, and psychotics are those who live in them. (Languid delivery after pregnant pause…) My mother cleaned them.” I’m sure her cleaning compulsions weren’t all her fault. Once Grandmommie told me that she warned Dot before they married, “J.C. is particular, and will be a demanding husband, not so easy to please.” Here in the background is his office; Momma and Daddy are sitting on the living room couch.

A good thing about the Gray House was that it had a den where we could sit and watch TV. (By the way, it was the same black and white set we had originally bought in Arkansas. We never had a color TV till after Daddy died. He didn’t see the point.) Before, at the Pink House, the only place I could sit was on my bed in my bedroom, since we weren’t allowed to use that living room and there was no den. I did sit at the breakfast room table sometimes to do my homework, but everybody always seemed to be either working or in their bedroom at that house, with no place to congregate.

At the Gray House, Daddy made himself an office in an extension off the living room. That little room, separated from the living room by some wooden columns, had windows on both ends and a brick floor leading to the original front door. (You can see it behind Momma and Daddy in the picture above.) The house was so old that there was a covered front porch for carriages outside this door.

The kitchen was all a light gray-green, and an odd thing about it was that the cabinets were metal, with a silver metal grid instead of solid shelves inside. In the kitchen cabinets were our same pink and white every day dishes that we seemed always to have had. I can’t call their names from memory, but I still have those dishes. The majority of the pieces were the “Printemps” pattern from Grindley, England, but some additional plates and serving dishes were from Villeroy & Boch, made in Germany and called “Burgenland”. Those say “Made in Germany” in English. I think they must have also been a post-War Germany purchase.

We used both clear and white glasses for water and milk which sat on a little short pedestal with a round base. I found out that these had been sold at the grocery store as containers for peanut butter and jam, and that’s how we collected our set. Those were the days of S&H Green Stamps, which you received each time you checked out at the grocery store. You licked and pasted them into a booklet and when it was filled up, it could be traded for various products that you wanted but might not be able to justify paying “good money” for. (Why did people call money “good” like that? I never knew.)

The kitchen sink faced the corner, with windows looking out to the patio on both sides of it. I don’t recall as much entertaining in that house as I did in the Pink House. We did have a wedding shower there for one of the college girls. That’s where I was introduced to cranberry bread and lemon bread, both of which thrilled my tastebuds. I’ve always loved lemons, but this was when I developed a fondness for cranberries.

On the other side of a counter in the middle of the kitchen was a large, long picnic table that had benches built into the wall around it on three sides. That’s where we ate most of our meals, and I have just a few memories of those years’ meals. One evening when Daddy had just come home from work, supper was put on the table, and Chip was home. He was discussing some novel thoughts or philosophy (I have no idea what the topic was), and Daddy became horrified at the possibility that Chip might actually believe what he was saying. Emotions ran high, and Chip finally said something like, “Dad, I’m just trying out ideas. I’m not always going to feel this way!”

In the Gray House, I was old enough to observe how Momma cooked, and I often judged that she was wrecking perfectly fine dishes by adding “weird” stuff to them. Cooking was one of the few places she allowed an adventuresome creativity to come out, and I didn’t appreciate it. I became aware that she was adding cornstarch to the saucepan when she cooked spinach, turning it slimy, and then she put boiled eggs on top, which I hated because I had developed a strong aversion to egg white. I pleaded with her not to “ruin” it like that, to no avail.

She would add wheat germ to things, or barley, or cornmeal, and it would wreck the texture. She was a Prevention magazine reader, and being her guinea pig for health food experimentation turned me off to what could have otherwise been a helpful education. She could be such a wonderful cook, but it seemed to me that she would try to punish us by making hideous “healthy” things we had to get through in order to deserve the incredibly wonderful dessert. I wish she had not been such a success at making peach cobbler and strawberry pie. This dichotomy made me just a little nuts about mealtimes.

I loved the plants at the Gray House, especially in the raised flower bed that ran under the kitchen and dining room windows. There were yellow and orange nasturtiums spilling out of those beds and hanging down to the flagstone floor of the patio. We had never grown those before, and I loved their strangely shaped leaves, reminding me of the Art Deco stylized depiction of nature. That patio was amazing. There was a curved, freestanding brick wall that contained a barbecue I think we never used, and enough room for several tables if we had them. (We didn’t.) We had a lemon tree and a pear tree in the yard that really produced, and magnolia trees with huge, fragrant blossoms.

Life in the Gray House was a strange period in our family. I was becoming a teenager, which is generally a strange time for anyone. Momma was taking on more responsibility at the library, and shifting more of the housework to me. One summer afternoon, I really upset her, probably by not completing some work I was expected to have done by the time she got home. When he arrived, Momma and Daddy had a meeting in the den and I tried to listen from across the kitchen in the laundry room, where I was ironing their sheets and his handkerchiefs.

When they were finished with their discussion, Daddy called me into the den and he laid down the law. I would not get my own way anymore. They would no longer change their plans to suit what I wanted. They would no longer accommodate me. They would do what they wanted. I would not disobey my mother. I would not talk back or speak disrespectfully to her.

He had no idea how good it felt to me for him to step in and take charge like that. He would never have imagined that I had been wishing that someone would put me in my place. Then they would be paying attention, taking their place as parents, and I would finally feel like a child, protected, and safe, instead of a miniature adult trying to “raise myself.” (On one of our visits to Nashville, Grandmommie had said to me in private, “Your parents aren’t going to be able to raise you, so you’ll just have to raise yourself.” This had sounded really scary and lonely to my ears.) Sadly, this “putting our foot down” period lasted mere weeks.

I took refuge in the books and movies and TV shows that pictured life as I thought it should be, as I dreamed it could be. I lived in the books by Louisa May Alcott, especially Little Women, and the series by Laura Ingalls Wilder that started with Little House in the Big Woods and ended with These Happy Golden Years. (Her work was later made even more popular by the TV series Little House on the Prairie.) I ate up the series by Elizabeth Enright that featured The Melendy Family. Happy family relationships were epitomized by the TV show that was my favorite, Father Knows Best. That series was in reruns in the daytime, and I would watch it every day around lunch time in the summers. I loved Danny Thomas in Make Room for Daddy, and Fred McMurray in My Three Sons, and the Dick Van Dyke Show. I only came to appreciate Andy and Barney of Mayberry after I moved to Nashville, but I would have enjoyed adding those shows to my regular “fantasy families” diet.

I also began to take refuge in music. I had always loved music, but now I started to receive a little allowance money and that’s what I chose to buy. I had a small collection of 45s that included the Doors “Light My Fire” and a bizarre rock version of “Ding, Dong, the Witch is Dead” from the score of the Wizard of Oz. Why I eventually sold all those 45s in a yard sale, I can’t imagine. I’ve lived to regret it.

We loved Peter, Paul and Mary. I didn’t know that the group was an invention of their manager, Albert Grossman, sort of an artificial creation like the Monkees. He pulled the group together in 1961, and Bob Dylan (whom he also managed for some time) and Joan Baez were becoming known around the same time. I didn’t delve into Dylan himself, but I would pick favorite songs from PP&M albums and discover that he had written them. My favorite album of theirs, Album 1700, also introduced me to John Denver, author of the PP&M hit “Leaving on a Jet Plane.” I loved the song “Bob Dylan’s Dream” so much I’ve included it in the Appendix in its entirety, as a great relic of the era. I loved “If I Had Wings” and “The Great Mandala”, both written by Peter Yarrow. What a rich collection of songs in one album!

PP&M’s next album, from 1968, was called Late Again, and there were two Dylan songs on it that became my favorites before I knew he wrote them: “Too Much of Nothing” and “I Shall Be Released”. That album also had a Tim Hardin classic, “Reason to Believe.” I’m so glad Matt introduced me to Tim Hardin’s first few records. He died young, and the pain he expressed in his music makes me think he died of a broken heart. What a writer! I was thrilled when the vibes that Farrell Morris chose to play on my first album reminded me of the sound of a Tim Hardin song.

I was still too ignorant to appreciate the history of the labor movement in America, and how music had played such a powerful role. I was only touched by the Great Depression in that my mother saved everything, and was inexplicably frugal. But I began to learn about these times, to get the feel of them, through the songs I would hear. Bob Dylan had pursued a relationship with Woody Guthrie, who was already so sick with Parkinson’s, and seemed to carry his mantle. The story is told that Allen Ginsberg, when he first heard Dylan sing, cried because he realized the baton had been passed to the next generation.

I had been exposed to a lot of classical music, and I kept wanting to point out to Daddy that there were classical elements in this rock n’ roll that he hated so much, like the organ solo in “Light My Fire”. He did appreciate one radio song of the era. He heard the banjo in Herman’s Hermits’ “Mrs. Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter” and he actually liked it! The banjo part brought back his Nashville roots, country roots he had put behind him.

In the summer of 1967 Momma and Daddy and I went on a family vacation to Catalina. We took the boat over to the island, fully dressed in our regular city clothes, and when we disembarked, I felt like I had arrived on another planet. All around us were semi-naked people with bronzed skin, and there was a spirit of ennui and woozy hedonism. I thought we must look to the natives like a family of Puritans. Some loudspeaker was blasting the Beatles’ “All You Need is Love” and we so painfully didn’t fit into the sunsoaked atmosphere, I wanted to curl up on the ground and disappear. I was mortified to be so pale of flesh, so conservatively clothed, and, worse of all, with my parents. This was the height of exquisite teenage suffering.

While we were living in the Gray House, the ‘Sixties were happening. I was too young to branch out on my own, and too desirous of my parents’ approval to openly rebel. It would be years later before I finally realized that I had never felt my parents’ approval. At this point I was still trying hard to win it, though not so very hopeful about the possibility of success. At any rate, my “hippie” leanings, though present, had to remain subtle. I wore love beads, but with a conservative dress. For Christmas, 1967, I asked for the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. (It had been released that summer.)

We had the Young family over for Christmas breakfast, a tradition which continued until my mom moved to Nashville in 1993. I wanted Matt and the girls to come upstairs and listen to the new Beatles album with me, but they weren’t into it. I was so excited about the record, I couldn’t wait until they had gone. I went upstairs alone and listened, feeling a bit of the alienation that was so well expressed on the album. “She’s leaving home, after living alone for so many years…”

I would try to imagine myself out and on my own, but I just couldn’t picture it. As a result of the Beatles’ musical explorations, I bought an album by Ravi Shankar, and turned off the lights and lit candles, but the sitar music and candlelight did not succeed in producing the desired effect. I was looking for a way out of myself, but I couldn’t find it – not like that.

Chip was now moving away from the family, first to return to Heidelberg for his junior year of college in 1965, and then to leave for good when he married Sharyn, a girl from Abilene Christian University. She had also gone to Heidelberg the same year with Pepperdine Year in Europe program, and there they met and fell in love. They got married in 1967, in their senior year. Emily Young and her husband to be, Steven Lemley, were also in the 1965 Heidelberg program, and the two couples have celebrated many of their wedding anniversaries together ever since. Sharyn and Emily are dear friends. Thus the Young/Moore connection established in the 1930s extends into the 21st century.

Chip actually proposed to Sharyn while at a special dinner out with Momma and Daddy and me. (He did at least take her off to another area of the restaurant to ask her.) When they were ready to get married, they flew to New York where Sharyn’s parents were living. Her dad was an IBM executive, so they lived in White Plains, a bedroom community for IBM’s headquarters in Armonk. Chip and Sharyn’s wedding was there and Momma and Daddy and I didn’t attend. I never understood what the deal was. It was the most important event in my brother’s life, and I was offended that my folks decided not to go.

I think I recall some level of disapproval of the marriage, maybe because they were both still in college, maybe because it was “too soon” after they had met in Heidelberg, who knows. My folks never said, I could just feel it. I wondered secretly if it was just because Chip was taking an independent stand that would remove him from their control. Maybe they just couldn’t imagine their little Chippy being old enough to have sex with a woman.

Nevertheless, while they were on their honeymoon, Daddy said, “Let’s you and me go to the grocery store and stock their refrigerator for when they get back home.” We had a lot of fun doing that, and I discovered that he had performed that thoughtful deed for several other young honeymooning couples.

After they had been back in town for awhile, we had a reception for them at our house. I can still see my mother wearing an ivory brocade suit, her hair freshly done at the beauty parlor in that once-weekly ritual, looking more prim and tense than usual, receiving the guests. We had a small white book with photographs from that party at our house, titled “My Son’s Wedding”. It struck me as very odd that we had no photos of the actual wedding that happened in New York.

Momma was having troubles of her own. Of course, I didn’t understand anything about it at the time, and the tendency amongst us had always been to blame me when there was family unhappiness. But this time, somehow, it was determined that she was the one who needed help. Help came in the form of a hysterectomy. Without much of an explanation, I found myself with my dad, visiting my mom in Daniel Freeman Hospital. She was looking really bad, lying in the bed hooked up to machines. Then she came home, and had to sit on a rubber “donut”. Nobody explained to me what had happened to her, or defined the word “hysterectomy” for me. I knew it sounded like “hysterical” and that made sense, because she was like that from time to time.

During the ‘Sixties, Norvel was dreaming big, fundraising, and mentoring a young golden boy named Bill Banowsky. He had no time to really interact with Daddy; he was too busy courting potential donors and raising millions of dollars. I think Daddy felt he didn’t get enough public credit for all he had done to make things work at Pepperdine. In his memorial talk after Daddy died, Norvel quoted him as having said, “It’s amazing how much a person can get done if he doesn’t care who gets the credit.” I know that’s the way Daddy tried to live. I suspect he was not fully able to. (I’ve added something Norvel wrote in memory of Daddy to the Appendix.)

Labor and maintenance weren’t sexy; building and fundraising were. Bill told me once that Norvel would dream, and then Bill would walk into my dad’s office and say, “Okay, J.C., how are we going to pay for this?” Somehow Daddy managed to make it all happen, what with wheeling, dealing, and building business relationships. One of those many business relationships was with the Buick dealership that rented their lot from Pepperdine. That’s why the Youngs, the Moores and several other Pepperdine families got good deals on their Buick leases. It was the first time we had leased a car, and the first time we had splurged and gone weekly to the car wash.

At some point in the mid-’Sixties, Daddy made a deal to purchase a new building for Pepperdine. It was actually an old, decrepit, abandoned building. It was on the corner of Vermont Avenue at 82nd or so. At one time, it had been a market place, with lots of small shops opening onto an interior atrium or courtyard. Daddy saw the potential, and had it gutted, repaired and redecorated. It would be an office building, so that the Administration Building on the main campus could be converted into classrooms. (Here's an outdoor graduation in front of the Administration Building, around 1963 - when I got my Brownie camera!) His office moved over to the newly remodeled building, as well as those of President Young and Vice President Banowsky, Admissions, and several other administrative services.

At some point in the mid-’Sixties, Daddy made a deal to purchase a new building for Pepperdine. It was actually an old, decrepit, abandoned building. It was on the corner of Vermont Avenue at 82nd or so. At one time, it had been a market place, with lots of small shops opening onto an interior atrium or courtyard. Daddy saw the potential, and had it gutted, repaired and redecorated. It would be an office building, so that the Administration Building on the main campus could be converted into classrooms. (Here's an outdoor graduation in front of the Administration Building, around 1963 - when I got my Brownie camera!) His office moved over to the newly remodeled building, as well as those of President Young and Vice President Banowsky, Admissions, and several other administrative services.To get to his office, you climbed a big set of stairs up to a second level – he was through a door on the right. There outside his door was a desk for a secretary, but he didn’t always have one. To go on to the higher administrative offices you went left, and then up another story. Daddy’s office had windows that overlooked the lower level, and being such a lover of stained glass, he had stained glass for those windows created in his favorite colors. They were the same style as we had in the church building – no pattern, no representation of any image, just a crazy quilt of color held together by the leading, brown and dark red and ochre and yellow and gold and green. Daddy was always a brown person, rather than black. One of our cars even looked like him to me, with its metallic brown body and beige roof.

Daddy and Momma both loved classical music. They made sure I listened to Peter and the Wolf and the 1812 Overture even when all we owned was a little portable record player in Arkansas. When Daddy would work late at the office or on a Saturday, he had a favorite album he played called Fifty Great Moments in Music. That’s how I learned so many famous musical themes, yet had no idea what they were called or who composed them.

There was a vacant, paved lot between this newly renovated building and the Buick dealership down the street. Sometime after the renovation, Daddy swung a deal to buy that lot, and he connected the Administration Building to the next building over with a tall, two-story or more high ceiling/roof. He designed archways to pass from this large hall to smaller rooms he had built on the far side of the hall. This meeting space became known as Fellowship Hall, and large gatherings were often held there. There would be faculty and staff appreciation dinners, fundraising dinners, and parties of all kinds. There would be dinners during the annual Lectureship, when people from all over California and other parts of the country would come together for a few days to hear various preachers and teachers.

During the lectureship one year there was a special program for little kids where they ran a Disney movie on a projector, and I loved that movie so much I was able to remember it decades later. When I finally was given a VCR (I had tried to put it off as long as possible, knowing what an addictive collector I could be), I made a list of movies I really wanted to tape from TV, and I would watch the cable guide to see if any of them were coming on. Just once in that period of focused and determined taping, this precious memory was aired, and I got to record the 1949 Disney magic of live action combined with animation, So Dear to My Heart. The same lady who played Jimmy Stewart’s mother in It’s A Wonderful Life, Beulah Bondi, was Granny in So Dear to My Heart, and a perfectly stern and tenderhearted Granny she was.

During the lectureship one year there was a special program for little kids where they ran a Disney movie on a projector, and I loved that movie so much I was able to remember it decades later. When I finally was given a VCR (I had tried to put it off as long as possible, knowing what an addictive collector I could be), I made a list of movies I really wanted to tape from TV, and I would watch the cable guide to see if any of them were coming on. Just once in that period of focused and determined taping, this precious memory was aired, and I got to record the 1949 Disney magic of live action combined with animation, So Dear to My Heart. The same lady who played Jimmy Stewart’s mother in It’s A Wonderful Life, Beulah Bondi, was Granny in So Dear to My Heart, and a perfectly stern and tenderhearted Granny she was.Speaking of the Lectureship, since this was an annual event, of course much of it runs together in memory. One moment does stand out. Bill Banowsky, Norvel’s protégé, was a young lawyer, so well spoken, intelligent and attractive that we all knew he would go far. One year, he challenged Anson Mount, an editor of Playboy magazine, to a debate on a popular topic of the day, “Situational Ethics”. This got national attention, and I listened in a lecture hall as he discussed the issues in a speech following the controversial debate.

I was impressed with his logic, and the intricacies of Bill’s thought. I especially appreciated his understanding of a burden I was carrying. He said, “You know, my boys (he had four) sit in front of the TV every day and absorb more shocking and emotionally weighty events than we ever did as children. And they have no power to respond. This causes them great internal conflict.” He understood how I felt! This began to answer the cry of my heart the night that I heard Kennedy was shot. I didn’t feel quite so weird for being deeply moved by international events.

Most notoriously, the annual AWP Gift Fair was held there in the Fellowship Hall, and in the connecting Administration Building. Unfortunately, seeing that annual parade of lovingly created donated stuff each year at the Gift Fair, I developed a real aversion to handcrafts and homemade items. In my immaturity, I missed the noble, sacrificial hearts behind all that effort, and only judged the artistic deficits I found. I had a strong tendency toward elitist arrogance that God would work on later.

Just across the corner from Daddy’s office on the same side of Vermont Avenue were a string of old Los Angeles storefronts, one of which was actually a real live Chinese laundry. I went there with him once to pick up his order, and was delighted to see the stacks and stacks of folded shirts on the ancient wooden shelves behind the counter. Men’s shirts fresh from the laundry seemed like treasures, so perfectly folded, with a piece of cardboard stuck inside to keep them straight. Those shirt cardboards found many uses around the home, not the least of which was my drawing.