There was another vacation site in the mountains east of L.A. that everyone seemed to visit at some point. It was called Arrowhead, and in those mountains was a retreat center called Mountain Home. After Lockhaven Christian School, I transferred to Airport Junior High, an extremely traumatic transition. I made a Christian friend through the choir named Eunice Mullisen. (That’s Eu-neece, not Eu-niss.) What a character – she reminded me even in eighth grade of an old lady. I decided she had spent too much time with her (relatively) elderly mother and not enough time with her peers. She was un-hip in the extreme.

Eunice was the first person I had ever spent time around who constantly called me by name. For some reason, our family had a habit of very rarely speaking anyone’s name. We would just speak directly to them, perhaps getting their attention with a preliminary sentence. But Eunice started many, many sentences with, “Gwen, did you know…” or “Gwen, I think…” or whatever. It irritated me! And I couldn’t have told you why. Later on, I decided that it felt a combination of manipulation (ingratiating, like she wanted something from me, like a salesman using my name as a false-intimacy technique) and offense (“Does she think I’m stupid that I don’t know she’s talking to me?”) Clearly, I’ve thought way too much about this minor irritation, and my reaction to it is disproportionately strong. But there you are.

Eunice invited me to come with her church youth group to Mountain Home for a week’s camping experience, and my parents allowed it. I was a very religious young person. At that age I was loyal to my status as a member of the Churches of Christ. While I was growing up, the leaders in that movement spent a great deal of energy emphasizing the distinctives that made us different from all the other denominations (including our claim that we were not a denomination, but the closest thing to the True Church, church like it was in the New Testament).

I don’t recall hearing very much about prayer, faith, salvation, sanctification, the power of the Holy Spirit, the development of personal character. Instead, we heard a lot about believers’ baptism by immersion vs. all the less acceptable forms of baptism used by the denominations. We were taught a cappella singing (the kosher “New Testament” way) vs. instrumental music (dangerously carnal, not to mention unscriptural). We believed in congregational autonomy vs. boards of governance, conferences, presbyteries, bishops, etc.; we had ministers or preachers vs. pastors, priests, etc.; and so on. I felt the need to bone up on Baptist doctrine before going to camp. I wanted to be prepared to argue and debate, should any issues come up where “we” disagreed with “them.” Thankfully, I never felt the need for debate arise.

This retreat center, Forest Home, was supposedly the place where the famous hymn “How Great Thou Art” was composed. The lyrics were carved on a huge piece of wood and displayed in the meeting hall at the center. The hymn was supposed to have some relation to Billy Graham, like it was his favorite song, or he got saved in a meeting where it was sung…something like that. Anyhow, all I knew was that I didn’t like it all that much. Was it because I knew it belonged to “them”? I loved “A Mighty Fortress is Our God” and I knew it was Lutheran. Who knows.

At camp one morning we were all encouraged to spend an hour alone. We were given a little pamphlet to read during that hour. It described how our hearts had rooms in them, and though we may have invited Jesus into some of the rooms, we might be keeping him out of others. I believe this was my first time to meditate on the concept of Jesus “living in my heart.” When I was a child, this was not exactly a Church of Christ idea. I think we didn’t talk much about the heart. Folks in the Churches of Christ at that time talked a whole lot more about “the Church” than we did about Jesus, or even God. That was about to change for me, but I didn’t know it yet.

Only three years later, how different things can be! This time, I was back at Forest Home with an altered point of view. My dad had died, and in the wake of his death my mom didn’t have much energy to worry about where I went or who I was with. I was allowed to rehearse and perform with a choir of my friends from high school. Under the direction of our high school choir conductor, Mr. Fontana, we premiered a terrific new piece of choral church music at Forest Home for a conference of choral conductors.

We rehearsed a few weeks for that event in the church where David Morales’ Firebranders rehearsed. Janice Hahn’s cousin Jackie Stalcup was dating Dave, so she was in the group. I especially remember Evelyn Ono and her friend Marcia Okawa. Evelyn actually had the chutzpah to walk out of rehearsal one day, because she was so angry at something – whether it was the horsing around and wasting time, or the choir’s lack of reverence for the music’s message, I’m not sure. I had never witnessed someone my age taking such a strong public stand.

It was the summer of 1969. After rehearsal one night, we walked over to the Hahns’ house near the church. We watched on TV while a man took his first step on the moon. It was so amazing to walk outside the house onto the lawn, look up at the moon, and try to comprehend that at that very moment a man was walking around up there. I missed my dad, who I knew would love to have witnessed that event. He was so excited a few years earlier to have me watch John Glenn broadcasting on live TV as he was orbiting the earth. I complained that the picture was too bad to know what I was seeing. I was unimpressed, and commented that Mr. Glenn looked like a monkey. I knew I disappointed my dad that I was so disinterested.

We didn’t take vacations when I was little because there wasn’t much money. But as Pepperdine prospered, we did better, and Momma and Daddy loved to travel, so we started a summer routine that lasted a few years. We drove up the coast past Santa Barbara and another hour or two to a quiet town called Paso Robles. Chip was with us on at least one of these trips, but after that it was just the three of us. There was a Spanish-style hacienda where we spent the night and had a nice supper. Not far from there, on the ocean, was San Simeon where William Randolph Hearst built his “castle”.

Hearst Castle was really an enclave, a compound where several different smaller mansions surrounded the giant one. Since I had already been to Europe and seen real castles, this one seemed a more accessible, American version. Mr. Hearst called the estate his “camp”, and he liked to keep it somewhat casual, with ketchup and mustard bottles sitting on the enormously long refectory table. He filled the mansions with paintings, sculptures, and architectural pieces from all over Europe, including ceilings, fireplaces and gargoyles. Someone commented that if such great American collectors as he had not bought up many of Europe’s treasures, they would have been lost to the public or destroyed in the World Wars. I love a quote from George Bernard Shaw, who was a guest of Mr. Hearst’s, “This is the way God would have done it – if He had the money.”

The next day, we drove on up to Carmel and Monterey. There was a hotel there, the Highlands Inn, that was my ideal for many years. I imagined having my honeymoon there. The cliffs above the ocean at Carmel are a bit like Scotland and Ireland, and the hotel was built in such a way as to provide the best of both worlds – the grand hotel’s luxury, and the cozy comfort of little bungalows. All along a hillside were paths leading to private cottages, and that’s where we stayed. The cottages had a bedroom and a sitting room with a working fireplace, so on misty cool nights you could have a fire in the fireplace. The internet reveals that there are no more little cottages, but the main hotel still sounds like a great place to stay.

Daddy was such a romantic about fireplaces. At the Gray House, where we were living by now, many nights we would turn up the air conditioner and have a fire in the fireplace in summer. When we were in the mountains at the cabin, we always had a fire, and it was one of my favorite things to set it up properly so it would burn well, and then poke at it and play with it to keep it hot. I actually became a bit of a pyromaniac, and played with fire so that a lump of burning plastic wrap once popped onto my hand. The burn left a “spoon-shaped scar,” as I described it in my little red Travel Abroad trip diary at the age of ten. (Daddy thought that description was clever and was amazed that I came up with it myself.)

In Carmel, we would stay in the cottage, but we would return to the hotel and eat our meals in their luxurious dining room. It overlooked the ocean, and the service was elegant, like the waiters in Europe, solicitous and dignified, which added to the pleasure of the food. There were shops in Carmel and Monterey that were fun to walk around, but mostly we did nothing while we were there but read in the cottage and walk. It was a nearly silent vacation, which both working parents needed, but it made me yearn for a relationship of my own.

Our church at Vermont Avenue was generally quiet. We didn’t go for rowdy melodies in our songs, and we didn’t usually have emotionally moving sermons. Everything was calm, and reverent, and reserved. So it was really unusual when a black preacher, Marshall Keeble, came to Pepperdine and lots of people gathered to hear him preach. There were so many people that we met in the Pepperdine Auditorium (which I knew well because of The King and I and the other musicals). I couldn’t have explained to you at that time what the difference was, but Bro. Keeble’s was the first emotionally stirring sermon I had ever heard.

At the end, he asked anyone who wanted God’s help to “come forward”. “Going forward” meant you stood up and walked to the front of the auditorium. Then you sat in the front pew and told the minister quietly what was on your heart. I was familiar with the practice of coming forward when a family had moved to town and wanted to “place membership” in a congregation. I was familiar with coming forward if somebody felt really, really guilty about something and wanted to “ask for the prayers of the church.”

I’m putting all these phrases in quotes because they were the standard phrases that members of the Churches of Christ would use for these things. I had never really heard what is commonly called an “altar call.” The Churches of Christ that I had attended or visited tried to downplay emotion. They always quoted the New Testament verse that everything should be done “decently and in order.” Emotional appeals and emotional responses were discouraged.

Just a moment’s “time out” to note one of the odd things about my religious upbringing. The Churches of Christ were firmly opposed to creeds, liturgy and repetitive formulations, teaching that those were things the “denominations” did and that God was not pleased with them. This could have been a response to Jesus’ statement that God’s children should not be like the Pharisees, thinking they would get God’s attention with their “vain repetitions.” (Matthew 6:7) At any rate, human nature and self-consciousness about public speaking led many men to unconsciously memorize phrases they had heard others use when they got up to pray, preside over communion, take an offering, etc. So we ended up doing the very thing we taught against. Since we traveled and visited other churches, I discovered that you could be in different congregations in different states and still here some of the same language used over and over.

One of my Nashville friends in later years cracked us up as he recalled the many pat phrases from his youth. “Heavenly Father, God of our Lord Jesus Christ, we come humbly before Thee this morning, asking that Thou wilt accept our prayers. We pray that Thou wilt bring to a ready recollection those things which our preacher has studied from Thy holy Word. May our worship be found pleasing in Thy sight. Guide, guard and direct us, and, if we have been found faithful, and in the end save us and grant us a home with Thee, is our prayer. In the name of Thy beloved Son and our Savior, Jesus Christ, Amen.”

Back to the Sunday when Marshall Keeble spoke, I was only nine years old. I had been raised in a family where my faults were pointed out on a daily basis. I wanted some relief from the guilt and hopelessness. I knew God was my only source of forgiveness. (Remember, my parents had told me when I was about five that they couldn’t help me in that department.) I knew I was a mess. My folks agreed that we would have a happy family if not for me. I was the problem. So I was desperate for God’s help. Bro. Keeble’s message offered hope, and of course I went forward!

When hundreds of people (all the rest of them being adults) made their way down front, someone decided that we should get a chance to speak about why we came, what we wanted from God, etc. So they asked all those who responded to move to the top floor of the Administration Building, where there was a smaller theater. There we could talk with Bro. Keeble. Even though I was the only child in the group, my heart was yearning after more of this experience, and I went with them. And I even had the passion or nerve or desperation to stand up in the midst of them and declare, “I need God’s help because I am a bad child and I want to be a better one. I want to be more obedient to my parents.”

That night, we were driving downtown to the Shrine Auditorium. I was in my usual place in the back seat of the car, and I decided to risk opening my heart to my folks and telling them what had happened to me that morning. I did, and their response is foggy to me. I know it was disappointing. They basically agreed that I needed to change. I didn’t sense that they were touched by what I had done.

0 ~ o ~ 0 ~ o ~ 0

When we were growing up, my family, the Youngs, and just about everybody else at Pepperdine were members of this movement, the Churches of Christ. When we kids were sent to Lockhaven Christian School, our parents had to explain about the existence of other churches and denominations. That school was operated by the Christian Church, an offshoot of a larger group called Disciples of Christ. We were the Southern offshoot of that movement, a division that occurred around the Civil War era, but we kids didn’t learn this at that age. There were also children in the school who were Baptists and Lutherans and various other flavors. Our parents didn’t teach us that we were the only Christians, but we were taught a lot about how our group was different from all the other groups. We didn’t think we were perfect, but we did suspect that we were more right than anybody else.

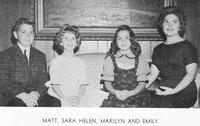

We went to church at the Vermont Avenue Church of Christ. We could walk there from home, because it was at the east end of the Pepperdine campus. College students always attended church there, and we girls liked knowing them. Helen and Norvel usually sat down front, in the second pew on the left. Norvel would often write an article for Power for Today or 20th Century Christian on a big yellow legal pad, and it was pretty obvious he wasn’t paying attention to the preacher. Sometimes my mom would scold him that he was setting a bad example by so obviously ignoring the sermon. Sometimes Helen was so tired that she would doze off, so she would have Marilyn or Sara sit next to her and rub her hands to keep her awake. Here's a picture of the Young kids around 1963.

We went to church at the Vermont Avenue Church of Christ. We could walk there from home, because it was at the east end of the Pepperdine campus. College students always attended church there, and we girls liked knowing them. Helen and Norvel usually sat down front, in the second pew on the left. Norvel would often write an article for Power for Today or 20th Century Christian on a big yellow legal pad, and it was pretty obvious he wasn’t paying attention to the preacher. Sometimes my mom would scold him that he was setting a bad example by so obviously ignoring the sermon. Sometimes Helen was so tired that she would doze off, so she would have Marilyn or Sara sit next to her and rub her hands to keep her awake. Here's a picture of the Young kids around 1963.I loved it when Norvel would be the guest preacher at Vermont. He was so enthused about what he was saying (which some of our preachers were not). One time he read a long passage from the Book of Acts, where Luke is describing a voyage at sea that he took with the apostle Paul. Norvel read it like he had been with them on the trip and was remembering it all, and he really made it come to life for me. He had such energy and imagination that he made me feel it. That had never happened to me in church before.

When I was little, I liked to sit between my mom and dad, and occupy myself by drawing. We girls also wrote notes to each other. We weren’t allowed to whisper. When we were little, we were required to be silent and sit very still. One thing I did sometimes was examine the contents of my mom’s purse. I found the items fascinating because they belonged to a grown-up lady. She had a dark brown alligator pocket book that zipped close, and a tan lizard skin bag that closed with a firm snap of a clasp. Those were my favorites because of their texture. She always had a tiny red New Testament and Psalms, and I liked to look at the fine print. And she always had Kleenex.

Little children were regularly carried out of services when they made any noise. Sometimes they knew a spanking was coming and starting freaking out in their parents’ arms as they were carried out. My parents didn’t often spank me, but once my mother whispered that she would give me a spanking after church. Knowing it was coming, I ran home, and when she came after me, I somehow had the nerve to run from her in the house as well. I think she gave up chasing me on that occasion.

I can’t imagine why she saved it, or how I found it, but I discovered in her papers a note from 1960. “J.C., Please do not let Gwen go to Helen’s or anywhere to play with children. She’s too tired to be good. I’ve just spanked her for talking back. If you can’t take care of her yourself, send her to the library to me.”

Daddy never spanked me. Momma later said that “he was afraid he would kill you children” if he spanked us. I only saw him rage once, and I can still see myself cowering down at his feet, clinging to his legs, not knowing for sure what exactly I had done wrong, but really feeling terrified. Instead of hitting us, Daddy would talk to us. Once Chip told Momma, “Please just spank me and get it over with. Don’t let Daddy talk to me.” That punishment must have seemed interminably excruciating to Chip.

I don’t know why I was such a “touchy feely” child. My parents were not affectionate or demonstrative, even with each other – I believe I only caught them once kissing in the kitchen. So where did I get the idea that I needed to hug everybody? Once when church was over and we stood up to leave, I reached out to hug Daddy. He stood there immovable as a barrel, allowing me to hug him, but not responding. I felt like something must be wrong with me that he wouldn’t hug me back.

The Young family and mine were always at church every Sunday morning, Sunday night and Wednesday night. That was the deal, if you were a serious Christian. We figured those who showed up only on Sunday mornings, and especially those who weren’t there every Sunday, must not take God very seriously. We couldn’t be too sure about their spiritual status. It was our duty to set a good example for others by making an appearance every time the doors were open. My dad was an elder, so that made our family’s image all the more important. People were watching. It must have been weird for my parents and the Youngs to attend church with people they had to work with during the week, but I didn’t think about that at the time – it was just our world.

One fun part of church-going was that it provided an excuse to eat out on Wednesday night. My mom worked full time but she was still supposed to get supper on the table every night on time. Thankfully, Daddy acknowledged that wasn’t feasible on Wednesday nights, and we went to a restaurant on Manchester Avenue called Du-Pars. It was really a coffee shop with a bar in back, but it seemed fancy to me. That’s where I fell in love with fried shrimp, and that’s where I invented squeezing lemon juice on a roll instead of butter and jam. In all my life I’ve still not run into anyone else who likes lemon juice on rolls. Du-Pars was where Daddy met with his Kiwanis group each week, a schmoozing and service organization for local businessmen. Daddy took me with him to the meeting a couple of times.

As I got older, I would beg Daddy to invite George Hill to supper with us. I knew if the three of us went alone, Momma or Daddy would be quiet or critical or frustrated or something unpleasant. But if George Hill, an entertaining single guy full of energy, went with us to supper, we would have fun. The adults would talk to each other and I could relax.

I can still feel all the feelings that came to me in the Vermont Avenue church building, three times a week for fourteen years. It was an old white stucco building. The wood trim was all dark brown. The pews were dark brown wood, padded with something like brown Naugahyde, or some other plasticized fabric. There was a central aisle, and an aisle on either side of the building. The side aisles were arched, like a smooth, rounded adobe house in the desert. Supporting the interior curve of the arches were round columns, with simple capitals connecting them to the main ceiling. This created a cloister effect on the side aisles. There were plain, round, brown metal chandeliers, with candle-like light bulbs, hanging down the center aisle of the building.

The church had stained glass windows, with no pattern or picture but a crazy quilt of pastel colors in all kinds of shapes. The stained glass artist or artists must have used broken pieces, fitting them together with the leading. I loved those windows. I loved how the Sunday morning light streamed through them. My dad loved stained glass so much that he had lights installed outside so we could all enjoy the colors during the evening services.

I loved the cool, calm feeling of sitting in that building during a service. It was quiet and safe, and the songs were beautiful. The congregation was mostly educated people, and the hymns tended toward a classical style. “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded,” “The Lord Is In His Holy Temple,” “Now The Day Is Over” (Marilyn loved to hear me sing the moving tenor part an octave up), and “Be Still My Soul” gave a sense of reverence to our worship. Dr. Earl Pullias, who had been a Pepperdine professor and now taught psychology at USC, sat on the fifth row back. I was told that he had been a big influence in our song leaders choosing the more dignified of the hymns.

I didn’t realize it growing up, but we looked down our noses at, or felt pity for, the little country churches, and the churches back in the South, the ones that sang the foot-stomping, thigh-slapping “oom-pah” songs. Those kinds of songs, we felt, lacked “reverence” but really we thought they mainly lacked class. In college, I finally discovered them for the first time, and I loved them. My boyfriend’s parents had a hymnal full of what they called “Stamps-Baxter” songs. (I believe that was the name of the publishing company.) The energy and joy in those songs fit my overflowing heart, newly baptized in the Holy Spirit. I am deeply grateful for all the hymns that shaped my childhood.

My beloved childhood preacher, Gordon Teel, told a story about a little congregation where the preaching was truly terrible. He noticed a little old lady who was faithful to attend week by week, year after year, and he, being a young whippersnapper at the time, asked her what kept her coming back. “It’s the hymns,” she said, “the theology in the hymns is so rich.” And it was for me too. The hymnal we used was a blue cloth-covered book with a blue string place marker, called Great Songs of the Church. When we were children, we didn’t realize that it was a collection of songs and hymns from many denominations. I still love that hymnal. It became my friend. I grew familiar with the names of the hymn writers and learned some of their histories.

In our tradition, the song leader would tell us the number of the “invitation hymn” before the sermon started, so we could find and mark it with the string. This was intended to make the transition from sermon to song smoother. It occurs to me that this was a technique intended to remove distraction, to produce an emotional effect, which the movement traditionally resisted doing. There was such concern that someone might have a merely “emotional” response to God, one that wouldn’t last, that we discouraged any emotional experiences at all in church.

After Gordon Teel had moved to another congregation, I didn’t like the preachers who followed him in the pulpit. Part of that was my age and my growing discomfort with our doctrine. I would occasionally read the Bible, trying to avoid criticizing the sermon in my head. How shocking it was to have my mom correct me for reading the Bible in church! She said I was supposed to be listening to the sermon. I found this bizarre, to be scolded for reading the Bible.

There were two chairs facing the audience on the platform where the pulpit stood. That’s where the song leader would sit between prayers, and where the men would sit who were making announcements or praying or whatever. As one of the elders of the church, Daddy went to regular meetings where they discussed budget, building maintenance, the preacher, the Sunday School, whatever they felt needed attention. An odd memory is that Daddy would get nervous about speaking before the congregation. Because he would cough when he got nervous, he kept a bottle of Terpinhydrate with codeine in his suit coat pocket to swig on. This habit seemed so opposite to my parents’ usual concern about what other people would think. My folks would never go in a bar or order wine in public, though my dad did keep a bottle of wine in the back of the refrigerator. He said a little shot glass of it helped him sleep. His conscience was clean because they had lived in Europe where people regularly drank with their meals, without the stigma American Christians put on drinking. Most Europeans didn’t drink to get drunk like Americans did.

In Sunday school it was a really big challenge to memorize all the books of the Bible. I think it was around fourth grade. That made it easier to find scriptures when we were looking them up in church and in school. We learned a lot of Bible stories. One Sunday School teacher was a college student, a gentle young woman named Dorcas Traylor. I knew the story of Dorcas from the Bible, what a good and generous woman she was, and this only heightened Dorcas’ stature in my eyes.

Once Dorcas asked us all to say who we wanted to grow up and be like. The other little girls went first, and each one said, “My mother.” When it was my turn, I said, “I want to grow up and be like you.” I was embarrassed to be the only one who didn’t want to be like their mother, but I also was a truth teller. I didn’t want to be unhappy or make other people so unhappy. I wanted to be nice. I had no idea that later Niceness would become an idol to me, and I would have to repent of worshiping it.

Knowing Helen Young in my growing up years moved my life closer to God. When we were little, our Wednesday night class was only Marilyn, Sara and me, and occasionally one or two other girls, so Helen decided to teach us instead of making us sit in church. We sat in little chairs around a table, and Helen talked to us. I remember feeling so special because an adult took the time to talk to me. My parents were always too tired or too busy or something. They never just sat and talked to me. Helen chose to take the time to impart things to her girls, lessons, family history, all kinds of training.

Here's a picture of Helen with her mother, Irene Maddox, and Pat Boone, taken around the time she was teaching our class. One of those Wednesday nights she talked about her mother, Irene Maddox, and she cried. I found out later she almost always cried when she talked about her mother. That night I learned a lot from watching and listening to her. I learned that it was okay to feel tender feelings and show them. I learned it was good to honor your parents and respect their example. I learned that when someone else has a close relationship with God, it makes you hungry to know Him better too. Both Mr. and Mrs. Maddox helped Helen want to know God, and she helped me to want to know God. She told us how her father was too old to play with her when she was growing up, but he helped her memorize whole chapters of the Bible. She said that this heritage meant more to her than if he had left her a fortune.

There was a “cry room” where mothers could take their babies and toddlers, up some stairs at the entrance to the church with a big plate glass window overlooking the congregation and a speaker system so the mothers could still hear the service. That’s where they put our Sunday School class for many years. One of our teachers, Ernest Shaw, had a boy and girl in our class who were shy, or at least quiet. We didn’t ever get to know them well. Mr. Shaw came to my dad once and told him I was prejudiced. I’ll bet I was, because later when I became sensitized to prejudice, I realized that my dad was really a racist. He was a product of a small east Tennessee town, even though his family had moved to Memphis, Mississippi and Nashville by the time he reached high school.

When we got older and found out that other churches had youth groups, we felt deprived. It was always hard for the elders to find teachers to teach our age group (no matter how old we were!) and I remember several adults and college students giving it a try. We were a tough audience! We were pretty critical and cynical, even more than is usual for teenagers, and very hard to “reach”.

We had one teacher who really tried hard, Jim Atkinson. I remember his seriously trying to teach us the book of Romans. When we got to the passage where it says God is like a potter and we are like the clay, and He can do with us whatever He chooses, it made me mad. I argued, “But surely God has to be fair! Surely God has to keep His promises!” I couldn’t handle it if God were like my parents, unpredictable and seemingly arbitrary in the way they acted. God just had to be different. I desperately needed Him to be dependable.

We probably hurt Mr. Atkinson’s feelings because we thought he was so uncool. His favorite word was “keen”, as in, “That’s really keen!” and we were so embarrassed for him because nobody said that word anymore. It had been popular maybe twenty years before. Once we were discussing popular singers and the name of Barbra Streisand came up. By that time, I had become aware of racism and prejudice. Mr. Atkinson told us that Jews like to spell their names differently than other people, and I got mad at him because I thought he was making an ethnic slur. I also scolded my mom for talking about “Jewing someone down,” by which she meant bargaining for a lower price.

Duane Doidge (a fraternity brother of Chip’s and Matt’s and Danny Jackson’s) taught our Sunday School one semester, but he gave up on us after not too long. Harry Skandera, another fraternity brother, tried it. No one ever really succeeded. I was so offended by one of our teachers. Bill Stivers was an elder, a professor of Spanish at Pepperdine, and led regular mission trips to San Felipe in Baja, California, and he taught our class for awhile. In a discussion on prayer, he said, “Prayer doesn’t really do anything to change God’s mind. It’s good for us psychologically, and that’s why we need to do it.” I was horrified, and thought the poor man had no faith. I believe I told him how that upset me.

Mr. Stivers caught me walking home after church one day and confided in me that his daughter Nina was not turning out as ladylike as he thought she should be. He asked me whether it was a good idea to buy her some false eyelashes and makeup. I heartily discouraged that. I didn’t like it that he was asking me for advice, and I didn’t like it that he wasn’t content with his daughter just the way she was. After my dad died, when I was sixteen, oddly enough Bill was the one I invited to take me to a father/daughter banquet. I guess he was the only man I thought could “act the part” and not be too uncomfortable escorting me…I perceived he had some compassion for me and wouldn’t mind too much. Below is a photo of Bill and me at that banquet.