More about the Youngs’ house, where I spent more of my waking hours than in my own home. (I only have this one picture, but I was delighted to find it! The house was torn down some years back when the campus was sold.) The big white house, its porches and its yards were like a playground for us kids. We ran all over the house, as well as all over the Pepperdine campus, making up stories to act out, and imagining all kinds of things. For awhile, the drama department stored their costumes in the attic off Marilyn’s room, and we played dress-up in those. One time some other Pepperdine faculty children were at the house with us, and on the huge front porch we acted out a play from a book. I had fallen in love with Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, and since those girls were always putting on plays, I instigated these.

More about the Youngs’ house, where I spent more of my waking hours than in my own home. (I only have this one picture, but I was delighted to find it! The house was torn down some years back when the campus was sold.) The big white house, its porches and its yards were like a playground for us kids. We ran all over the house, as well as all over the Pepperdine campus, making up stories to act out, and imagining all kinds of things. For awhile, the drama department stored their costumes in the attic off Marilyn’s room, and we played dress-up in those. One time some other Pepperdine faculty children were at the house with us, and on the huge front porch we acted out a play from a book. I had fallen in love with Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, and since those girls were always putting on plays, I instigated these.One story I remember trying to make into a play was “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep”, a Rudyard Kipling tale about a little orphaned boy who is severely mistreated. I related to his pain so deeply that I wanted to act out his drama. Marilyn and Sara, not having read the story nor having experienced the same pain, could hardly have been expected to catch on, but I tried directing them anyway.

Besides the two attics, the house had a full basement, and that meant a whole lot of scary, dark, mostly empty, cold rooms. Chip thinks there were fourteen rooms -- I was too scared to go in all of them and count. He says there was a nine-pin bowling alley in one of the basement rooms. He also recalls that there was a wireless set from World War II, and a real Edison-style wax recorder that actually worked when he first saw it.

For awhile there were different college guys living in the Youngs’ basement. One was named John Carothers. He was studying to be a doctor, and was the son of some friends of the Youngs and my parents in Nashville. (His dad, Lip Carothers, was an executive for American Airlines, so of course for many years I felt that American was the airline of choice.) John was very interested in Sara. He told her he was going to wait until she was grown up enough, and then he would marry her.

Sara always seemed to have that effect on certain young men, and I think Marilyn, being fourteen months older, was understandably jealous of that. I know I was -- I was always wishing I could overhear what they were talking about so maybe I could catch on to how Sara attracted them and then held their attention. I never learned how to flirt, and she was such a natural at it.

Marilyn and I used to sit and talk in the dark, when I would spend the night. Even as early as ten years old, we dreamed about how wonderful it would be to someday have a man to talk to, to share heart to heart with. Marilyn couldn’t have imagined, when we were young, what a wonderful man God was saving for her to love. And she would have been more than horrified to hear how long her wait would be! She was forty when she married Stephen, after a few bad relationships, followed by ten celibate years of declaring to everyone that God was going to bring her a strong Christian husband.

Back to that basement. When we got to be pre-teens, we used the biggest basement room as our meeting place for a group we formed called the “Associated Girls for Pepperdine”. (This was an adjunct organization to its parent, Associated Women for Pepperdine, which had been founded by Helen Young and for which she and my mom both served terms as President.) The members were Marilyn, Sara, Susan Teague, me, and Honorary Member Weldon Blackwell. (Weldon was a boy, but he really wanted to join so we let him.) Since there were usually just four girls (sometimes Beth Ross would also join us but not often), we had just enough officer positions to go around, so we would rotate being President, Vice-President, Secretary and Treasurer.

We had regular weekly meetings during which we tried to observe Roberts’ Rules of Order (except that we weren’t exactly sure what they were). One year we even had a booth at the Gift Fair, the AWP’s annual fundraiser, where we sold what we had baked together in Helen’s kitchen. It was the late ‘Sixties, so we also

sold candles we had made as well, and we had incense burning and Judy Collins music playing, and I think it made some of the older ladies quite nervous. We raised $80 for the Pepperdine Scholarship Fund, which we presented formally to Norvel. Somewhere there’s a publicity picture of the presentation of that check. Helen always did her part to make the Gift Fair successful by buying things that were still unsold when it ended. We girls always laughed about the horrible homemade treasures in the “Gift Fair” closet which Helen would then attempt to give away as gifts throughout the year. We became cultural snobs at an early age, but I claim the title as the worst in that regard.

sold candles we had made as well, and we had incense burning and Judy Collins music playing, and I think it made some of the older ladies quite nervous. We raised $80 for the Pepperdine Scholarship Fund, which we presented formally to Norvel. Somewhere there’s a publicity picture of the presentation of that check. Helen always did her part to make the Gift Fair successful by buying things that were still unsold when it ended. We girls always laughed about the horrible homemade treasures in the “Gift Fair” closet which Helen would then attempt to give away as gifts throughout the year. We became cultural snobs at an early age, but I claim the title as the worst in that regard.0 ~ o ~ 0 ~ o ~ 0

The front entrance was rather grand. The big, heavy carved wooden front door, which opened onto the formal living room, was used mostly when company came to visit. From the driveway, there was a walk, and you could come up the stairs from that side or from the side yard to a center landing where the stairs met, then turn and climb more stairs to the front door. The porch had two large arches, one on either side of the doorway, and was as spacious as a large room. All of the stairs and porches were a reddish colored tile, not shiny with glaze but a matte-finish clay tile.

From the driveway, we would usually come into the house through the side door, to the family room, or the back door which led through a hallway to the kitchen. Those doors were hardly ever locked. Either way, you had to climb a flight of stairs. The steps to the kitchen went straight up to the door, but the stairs to the family room led first to a wide side porch, which rounded the corner to become the front porch. That side porch and entrance was built back when people drove horses pulling a buggy or carriage. Tthe driveway next to the family room door was covered with a wide archway that would keep you from getting wet if it rained.

If you came up the stairs to the family room, you might be tempted to be a little dramatic or playful and walk out on one of the two wide, white ledges on the outside of the stairs. Sara often did that. Also, when we were a little older, she like to come and go from the family room to the porch through a long window instead of using the door. The door to the family room had glass panes, so you could peek in and see if it looked like anyone was home.

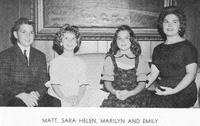

In the family room was Helen’s desk, near the side door, where she could often be found of a morning helping the girls make last-minute adjustments to their homework. There were also a couch, a TV and a stereo. We spent many, many hours there listening to music, playing records on that turntable. One of my happy memories of the family room was signing and addressing Christmas cards. All the kids, Emily, Matt, Marilyn, Sara and I were sitting with index cards in boxes and complaining about how many there were to do, and of course there was Christmas music playing on the stereo. Here's the picture of the kids that was inside that Christmas card. When she was little, they used to call Sara by her full name, Sara Helen.

In the family room was Helen’s desk, near the side door, where she could often be found of a morning helping the girls make last-minute adjustments to their homework. There were also a couch, a TV and a stereo. We spent many, many hours there listening to music, playing records on that turntable. One of my happy memories of the family room was signing and addressing Christmas cards. All the kids, Emily, Matt, Marilyn, Sara and I were sitting with index cards in boxes and complaining about how many there were to do, and of course there was Christmas music playing on the stereo. Here's the picture of the kids that was inside that Christmas card. When she was little, they used to call Sara by her full name, Sara Helen.

It could be that the reader has never seen a record player or stereo system. It’s what we used back then to listen to music, before cassettes and CD players and MP3s and iPods. When record albums had been used much, they would develop scratches. I became a fanatic about cleaning the dust off them before I played them, trying to keep finger prints off, and always putting them up correctly in their slipcovers. But even then my ears were bothered by the scratches and distortions. I told myself there was a crackling fire in an imaginary fireplace, and that helped some.

From the family room, you could go down a dark hall to the right, to Norvel and Helen’s bedroom and bath, or straight ahead to the living room, or to the left to the study. The study connected the family room to the living room. It faced the front of the house and had big glass French doors (those doors that come in pairs and open together) which led to the front porch. Those doors were always locked. The study was where Mrs. Young’s secretary would work at a huge desk. There was a leather-covered bench built into the wall, with a dark wooden back that hid behind it a fold-down bed. Once Marilyn was sick with measles and was allowed to sleep there so her mom could keep an eye on her.

When we were little, people used manual and electric typewriters instead of computers. There was an IBM Selectric on that desk where we could type. A Selectric typewriter had little balls that you could change to make the type look different. Even then I thought it was cool that you could have a choice of fonts. (Years later I would become a font addict.) My dad must have thought it was cool too, because he had a typewriter that was cursive and he used it for all his correspondence, which he proudly typed himself. I remember using carbon paper to make copies, and I thought Whiteout was a wonderful thing until I learned how to use the correction tape in the Selectric! I never did learn to type without errors.

A dark wood-paneled hallway ran between the family room and Helen and Norvel’s bedroom. There was a walk-in closet on the right side of that hallway that was filled to the ceiling with overflowing bookcases. That closet had a window too. I loved that cramped, stuffed closet. One of my favorite books that lived there was the thick, blue cloth-covered Etiquette by Emily Post. I loved to look at the old black and white photographs of how life used to be in the days of elegance and propriety. (I didn’t realize it had only been a few years since all this grandeur had been promoted as the standard for the upper middle class way of life.) I would read with amazement Mrs. Post’s long lists of all the requirements for a properly outfitted home. I guessed it was important to familiarize yourself with Mrs. Post’s Etiquette if you didn’t want to embarrass yourself in company.

Also in that closet was a complete set of the little magazine we called “Power”, but officially known as Power for Today, bound in black. The Youngs founded this periodical back when most all their friends were single or newlyweds and had lots of time and energy to volunteer their help. It was Norvel’s vision that Christianity was demonstrably relevant to modern culture and must be shown to be so. He and Helen edited this devotional magazine, and a small monthly magazine called 20th Century Christian. Who would have guessed at its founding that my dad’s youngest brother, and now my cousin Carol, would carry that business into the 21st century? I’ve been trained to think all my life, when special God-moments happen, “Oh, that would make a great Power article!” But I’ve not written for the publication, because I left the denomination early and the readership would not consider me a kosher contributor. The Youngs’ daughter Emily and her husband, Steven Lemley, are co-editors today.

There was an old-fashioned white-tiled bathroom, and then came the bedroom. The Youngs had a king-size bed. I think they must have bought one of the earliest electric adjustable beds, where you could push a button and make the head or foot of the bed rise. Dr. Young (as I always called Norvel) loved to be in his pajamas as often as possible, sitting in that bed with the head and feet raised so it was more like a lounge chair. He would read the paper, write articles, watch TV, eat pretzels or pistachio nuts, and welcome all of us to gather in his and Helen’s bedroom.

As I got a little bit older I grew amazed that they were so willing, since I wasn’t their child, to let me be there with them in their pajamas, but they never acted embarrassed or uncomfortable. If you knocked on a door, or called out to find out who was home, Helen would call, “Come!” with such a warm, energetic voice that she always made me feel welcome.

This delightful sense of being welcomed and accepted was threatened when my mother told me, “The Youngs won’t tell you when you’re not wanted.” She knew that Helen was so ruled by her desire to be generous and gracious that it would be hard for her to tell the truth and ask me to go home. But I couldn’t bear the thought that this acceptance I so desperately desired was not to be trusted. So I rejected her wisdom as mere bitterness or jealousy. Years later, I came to understand how I hurt my mother, and added to her already strong self-rejection, by comparing her with Helen. I repented to her, but it was too late to undo the damage I had done.

Over the Youngs’ bed hung a big painting of the prophet Samuel as a little boy, kneeling and talking to God. As Helen explained, that was when Samuel was living with the priest Eli and learning how to serve God. One night he heard God speak to him. Eli coached Samuel to answer when God called to him, “Speak, Lord, for Your servant hears.”

There was a dressing room off the bedroom for Helen and another large closet for Norvel. I always thought Helen’s dressing room was glamorous because she had lots of beautiful clothes and she used more makeup than my mom did. It was always pretty messy in there, because she was always in a hurry to get on to the next thing. That messiness was a shock to me, because my mother was very careful about everything being in its proper place, but Helen seemed delightfully unaware of such restrictions.

From the side door, it was a straight shot through the family room, through the living room, and into the guest wing with two bedrooms and a bathroom between them. The big blue guestroom was very elegant and had a double bed and a blue velvet covered window seat, and the beige bedroom had twin beds and rich drapes. That’s where Grandmother Mattox would stay when she visited. Here she is with daughter Helen Young and a popular singer and actor of the day, Pat Boone.

One Christmas, Mrs. Mattox was visiting. She was the first person I had ever known who was so old, and she was losing her eyesight. It made me feel a bit strange to be around her because of my unfamiliarity with blindness, but I found she was easy to talk to, very awake and aware. She liked to listen to the news and discuss current events. We were all helping to decorate the Christmas tree. She was sitting in a chair and unpacking glass ornaments from a box when one broke and cut her finger. She was bleeding, and someone ran to get a bandage. Sara said, “Grandmother, doesn’t it hurt?” and she said, “No, dear, when you get as old as I am, little accidents don’t hurt as much.” I found that piece of information fascinating.

The living room was a long room, with dark wood paneling and a fireplace at one end with green tiles around it. Every year I was impressed with how tall the Youngs’ Christmas tree was. It touched the ceiling of the living room, and that was a high ceiling, maybe fifteen feet. One Christmas when we were little, Santa Claus brought each girl a doll called a “Patty Play Pal”. The dolls were almost as tall as we were, and we were so excited to have them. In the living room there were gas heaters built into the walls, and one of us (I don’t remember which) got our Patty Play Pal too close to the heater and burned her hair. What a smell!

The living room was a long room, with dark wood paneling and a fireplace at one end with green tiles around it. Every year I was impressed with how tall the Youngs’ Christmas tree was. It touched the ceiling of the living room, and that was a high ceiling, maybe fifteen feet. One Christmas when we were little, Santa Claus brought each girl a doll called a “Patty Play Pal”. The dolls were almost as tall as we were, and we were so excited to have them. In the living room there were gas heaters built into the walls, and one of us (I don’t remember which) got our Patty Play Pal too close to the heater and burned her hair. What a smell!Nearly every little girl in the ‘Sixties seemed to have a Barbie doll. I had one, and I had a blue plastic case to keep her and her clothes in. I didn’t have many store bought clothes for her, but my grandmother Whitesell had a sister, Aunt Bess, who loved to sew. She would tailor exquisite doll clothes to fit Barbie and mail them to me. They were works of art, especially the white satin wedding dress. One summer while I was visiting in Nashville, Aunt Bess let me sew with her and we picked out fabric and made a tiny eight-patch quilt to fit Barbie’s bed. I still have the little quilt, though Barbie is long gone.

Back at the Youngs’ house, the way you turned on the lights in this house was with push buttons, instead of light switches. I’ve never seen another house wired like that. From the living room you could also enter the Music Room, which had some formal chairs, an embroidered day bed, and a grand piano with the lid elegantly up. The Young girls took piano lessons for awhile, and the three of us would try to impress each other with what we could play, but I was always the best until Janice Hahn started going to school with us in seventh grade. Janice outshone me on the piano and won Marilyn’s admiration.

But before that, here’s a mental video I have of the Music Room. We girls were sitting around the room in stiff formal wooden chairs, and Emily (Sara and Marilyn’s older sister) was teaching us deportment. We were to sit with our knees together, legs pointing at an angle, and our feet crossed at the ankles. Our hands were to lie in our lap just so. We even did the walking-with-the-book-on-your-head thing. I asked Emily, “When are our knees going to stop being so knobby and get all round like yours are?” I had no idea of it at the time, but this may have mortified her, because she was already a bit self-conscious about weight.

This lesson from Emily was one in a series that our parents put together one summer. They decided that our AGP club (Remember the Associated Girls for Pepperdine?) could be useful, and that we needed some scheduled activities to enrich us. So we took a typing class that summer, we took some art classes in the Pepperdine art department, we went to Peggy Teague’s house (her husband Bill was Vice President of Pepperdine at the time) and learned how to wrap gift packages (I still think of that lesson when I wrap packages), and we had that deportment class with Emily. I actually enjoyed the attention and the activities a lot, and wished we could have had more summers like that. But the grownups only got it together for us that once.

If you left the family room and turned right, you entered the formal dining room (the one with the aforementioned mysterious stain around the chandelier), where we only ate on special occasions. Then there was the butler’s pantry, which was a little hallway with cupboards and shelves, and then the swinging door to the kitchen.

The kitchen was all white and had a white Formica-covered table in the middle. In the refrigerator you could usually find all kinds of leftovers. Leftovers from teas and dinners, leftovers from receptions and breakfasts. We could usually scrounge around and find things to snack on. You had to be careful of the milk though, and check it before you chugged it. (It might be sour.) I loved to go shopping with Helen and the girls at a huge membership discount store called Fedco. We would load up two grocery carts with all kinds of things, always including big cases of canned diet soda. I especially loved Fedco when I started buying record albums there at $3 each.

When we were very young, Helen had a lady helping her with the housework whose name was Valeria. She was from an eastern European country, like Poland or Czechoslovakia. I don’t remember if she cooked for the family, but she probably did. I do remember her being gentle, quiet and shy, maybe because she didn’t speak much English.

After a few years Valeria left, and we got Geraldine. Geraldine was a real character. She was very bossy, loud, mouthy and set in her ways. She enjoyed watching “her stories” (the soap operas on afternoon TV) while she ironed, and she enjoyed complaining about how messy the kids were. She would often cook a main dish for the family’s supper, like a roasting pan of barbecued chicken, and leave it in the refrigerator. Geraldine made absolutely the best cookie dough I have ever tasted, and I’ve always wished I had her recipe. A roll of it would be in the freezer waiting for someone to get it out and bake some cookies. I would sneak little bites from it, and probably more than once ate a big wad of it. It was fantastic.

Once a child of Geraldine’s, I think it was a son, was in a fight or got shot and was taken to L. A. County General. It must have been summer, because it was daytime when the girls and I drove downtown with Helen to be with Geraldine in the waiting room. County General was enormous, and it took us a long time to find her. There were different colored stripes painted on the floor that you could follow to different parts of the hospital, and in some of the bigger halls the stripes were seven or eight or nine colors.

I thought, “This is really something, that Mrs. Young would take the time to drive all the way down here and bring us just to show Geraldine that she cares about her and her child.” My mom just wasn’t the kind of person who got involved in someone’s life like that. She didn’t want to meet my friends or their parents, and she rarely did anything for her cleaning women, when later on we could afford someone once a week, other than pay them.

The first dog the Youngs had was named Stonewall Jackson. They made a house for him by the steps down from the breakfast room. Later on, Marilyn had a dog she kept for years, named Buckwheat. Geraldine really disliked Buckwheat. He was a tan and white beagle, hefty and low to the ground. Buckwheat had some digestion problems, so if there was ever a bad smell in the air, we would always say, “Buckwheat did it!” and that way no one had to own up to passing gas. In the Young family, flatulence was called “bluffing”. “Who bluffed?” was a question often heard. Buckwheat would wake us up at night scratching his back on the frame of Marilyn’s bed. She really loved that dog.

Buckwheat was a racist, and it may have been based on experience, since there were black kids in the neighborhood who would ride their bikes and chase or kick him. It was an unfortunate name for a dog to have in the racially tense ‘Sixties in Los Angeles. “Hey, Buckwheat!” was not something that should be shouted in a neighborhood next door to Watts, where the riots and fires happened in 1965, and where Pepperdine had its own racial crisis two years later. Buckwheat lived long enough to move with the family to Malibu in 1972, and lost a lot of weight chasing animals and running all around the beach house property. Finally he was hit by a car on Pacific Coast Highway, and Helen put him in the freezer so Marilyn could give him a decent burial when she came home from college in Abilene, Texas for a visit.

Back to the big white mansion in L.A. In the kitchen, to the right of the sink in the windowsill, Helen kept a box of index cards that had encouraging words written or typed on them. She had collected verses from the Bible and quotes from wise people, so there would always be something encouraging for her to think about while washing the dishes or fixing meals. A plaque hung on the kitchen wall that had a prayer of Reinhold Niebuhr which people now call the Serenity Prayer: “O God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” We could not have guessed when we were kids how much those words would come to mean to us in later years.

One funny thing to me about that kitchen was that there was always a mess somewhere. Maybe the top was left off the ketchup bottle or the pickle jar and they’d be sitting like that in the cabinet. Or there would be a spill from a cupboard dripping onto the counter. Or one of the kids would pour a glass of milk and it would end up half in the glass and half on the table or on the floor. My mom liked things neat and clean, so Chip and I always had to be very careful. I thought it was kind of wonderful that the Young kids were free of that tight restriction – although I was also horrified by the messiness.

As we got a bit older, the kids drank “Instant Breakfast” in the morning, which was a chocolate flavored powder that you stirred into milk, or “Sego” which was one of the early canned diet meal drinks. We were always in a big hurry to get to school in the mornings. It was so hard to wake Marilyn up, and then there was that last minute homework. (I never had last-minute homework, but that’s how the family often managed at the Youngs’ house.) There was certainly no time to eat breakfast if you had to sit down to do it.

By the time we got to seventh grade, we were always going on diets. There was the grapefruit diet, where we ate a half a grapefruit with every meal. For that one, I was actually allowed to spend one whole week with the girls, eating together and running around the track behind the house every day. We were very diligent – for that week! But it was hard for all of us to stick with anything much longer than that.

Being so often restricted at home on what I could eat, coupled with my early association of comfort with food, encouraged a sneakiness in me. But I had a mother one could not easily get past. Sometimes she was incredibly conscious of what she had in the kitchen and the freezer. Once she came home from work and hollered, “There were thirteen cookies in the cabinet and now there are only ten! I want to know who ate them!!” On another occasion I asked if I could have some grapes and she responded, “Yes. Six.” Something rose up in me that said, “I’d rather have no grapes than eat just six!” The atmosphere was so controlling that I sadly came to associate bounty with freedom, and restriction with being deprived. It took me a long time to retrain myself.

After the kitchen came the breakfast room, where sit-down-together meals were usually eaten (rarely, like Sunday lunches after church). From there, or from the side door hallway, you got into Matt’s rooms. He had two rooms and a bathroom, like a little apartment of his own. I have a vague memory of my brother Chip and Matt tying me up in a chair and leaving me back there one time. I think I was pretty little at that point.

In my teenage years, I thought Matt’s rooms were very mysterious and fascinating and would wander (Shall we say sneak?) around in them, or sit and read his books when he wasn’t there. That’s where I made the acquaintance of J. D. Salinger and his Franny and Zooey. (That’s why Danny Jackson says he noticed me for the first time. He was impressed when Matt told him that I had read all of Franny and Zooey in just one long, delightful afternoon.)

No comments:

Post a Comment